Why this massive rail company believes hydrogen could be the future of train travel

Rail is having a moment in the U.S. But amid talk of electric commuter trains and new high speed passenger lines, freight rail doesn’t often make the headlines. Still, it’s an industry ripe for innovation, and one of the largest locomotive manufacturers is moving that way. Wabtec, which has 25,000 locomotives operating in North America, is developing an engine that can be powered by hydrogen and diesel, which would be an important step in reducing emissions. Freight rail is currently responsible for 1.8% of the carbon emissions from transportation in the U.S., according to the EPA. Broadly, the railroad industry has made fuel efficiency gains in recent years. According to the Association of American Railroads, a gallon of fuel powers one ton of freight for almost 500 miles—three to four times more than a truck. Freight trains became 47% more fuel efficient between 1990 and 2020. “Railroads are already very efficient. They’re producing relatively few emissions per ton of freight transported over distance compared to alternative modes,” says C. Tyler Dick, a professor at UT Austin who researches railroad energy technologies. “But, like everyone else, there’s this incentive to try and further reduce the energy consumption and associated emissions with them.” Wabtec aims to retrofit existing engines to use a blend of diesel and hydrogen fuel, which Chief Technology Officer Eric Gerbhardt says would reduce the carbon emissions by 80%. But the company says it will be several years until its first retrofitted locomotive is commercially available and at least 2030 before the economics of hydrogen make sense for a broader rollout. Availability of clean hydrogen Locomotives last between 30 to 40 years, and rail companies aren’t inclined to swap in new versions of the expensive equipment early. By modifying the existing locomotives to use hydrogen, Wabtec hopes to speed up the adoption of alternative fuels. “It gives optionality, because our hypothesis is that these fuels are not going to be available everywhere all at once,” Gebhardt says. Indeed, availability is a key concern. Approximately 10 billion kilograms of hydrogen is produced in the U.S. every year—the equivalent of 10 billion gallons of fuel. Powering U.S. freight rail required 3.1 billion gallons of fuel in 2022. However, trucks—a potential competitor for hydrogen fuel—used 172 billion gallons of fuel that same year. In other words, the amount of hydrogen currently being produced in the U.S. is a drop in the bucket of what would ultimately be needed. The federal government is trying to help solve this issue. As a part of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, $8 billion was earmarked for hydrogen hubs across the country. There’s also the fact that hydrogen isn’t necessarily a clean fuel. While it produces no carbon dioxide, it requires a lot of electricity to produce—and that energy can come from clean or dirty sources. “In some cases, depending on where that electricity is coming from, you are actually creating more emissions than if you just had a diesel engine on the locomotive providing that power,” Dick said. Green hydrogen is rare at the moment (95% is made using natural gas, which comes with significant emissions), but as production scales up, that could change. Hydrogen also presents safety challenges, as it’s a very small, very flammable molecule prone to finding its way through cracks in storage containers. Dick says these containers would require a cryogenic component to keep the hydrogen at a low enough temperature to maintain its density. Wabtec plans to have a car behind the locomotive that would carry the hydrogen at a low temperature. Wabtec’s hydrogen powered engine. [Photo: courtesy Wabtec] Lowering Rail Emissions Regulators and shippers seeking to reduce carbon emissions have pushed the industry to clean up its operation. Last year, for example, California passed regulations requiring all freight rail locomotives built after 2035 to be zero-emission. Right now, the vast majority of freight and passenger rail operations in the U.S. are powered by diesel. In addition to hydrogen, companies are looking at a range of alternatives, including battery, overhead electric, renewable diesel, and biodiesel. [Image: Wabtec] While Dick says overhead electric would be three to four times more efficient than using electricity to produce hydrogen, it would require a massive investment to update rail infrastructure across the country. Wabtec says the lack of infrastructure is why it’s not currently investing in electric freight trains. A transition from diesel to hydrogen fuel offers some unique advantages, Dick said. The actual process of fueling is similar. With a diesel engine, the train pulls into the station, and fills up its 5,000 gallon tank with a hose in 20 to 30 minutes, Dick said. The process with hydrogen would be similar—albeit with a molecule that’s more of a

Rail is having a moment in the U.S. But amid talk of electric commuter trains and new high speed passenger lines, freight rail doesn’t often make the headlines. Still, it’s an industry ripe for innovation, and one of the largest locomotive manufacturers is moving that way.

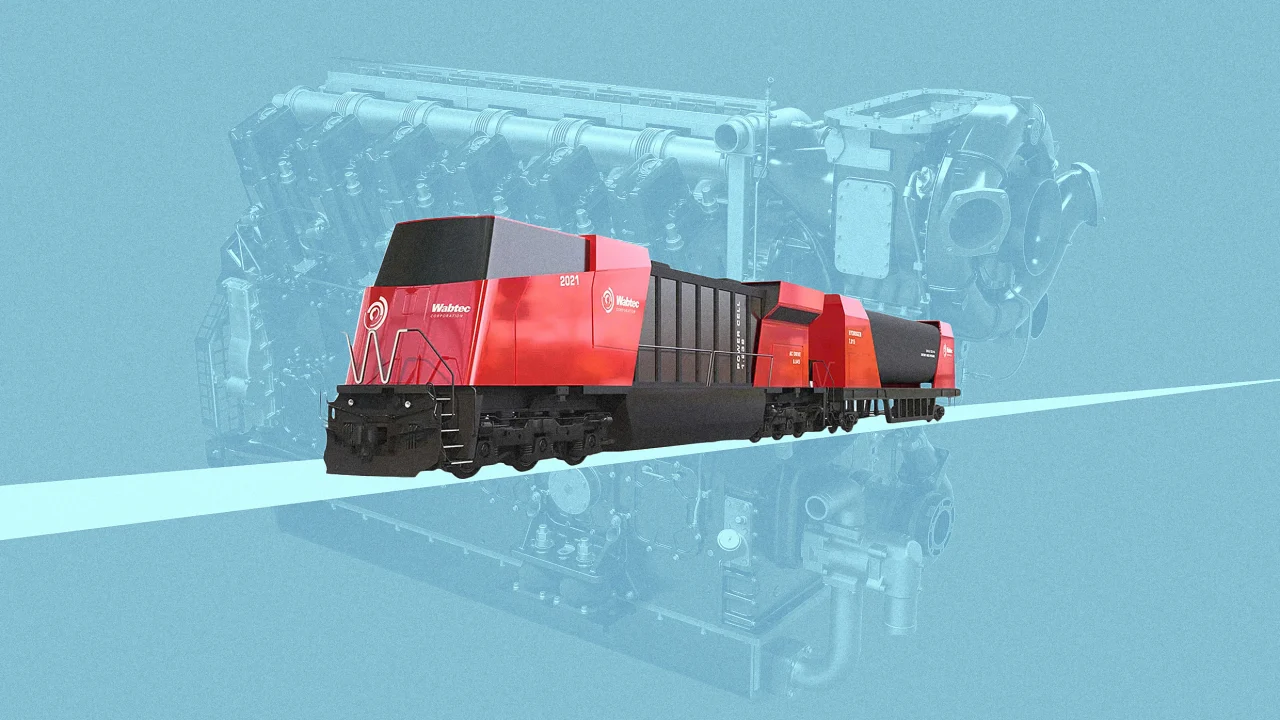

Wabtec, which has 25,000 locomotives operating in North America, is developing an engine that can be powered by hydrogen and diesel, which would be an important step in reducing emissions.

Freight rail is currently responsible for 1.8% of the carbon emissions from transportation in the U.S., according to the EPA.

Broadly, the railroad industry has made fuel efficiency gains in recent years. According to the Association of American Railroads, a gallon of fuel powers one ton of freight for almost 500 miles—three to four times more than a truck. Freight trains became 47% more fuel efficient between 1990 and 2020.

“Railroads are already very efficient. They’re producing relatively few emissions per ton of freight transported over distance compared to alternative modes,” says C. Tyler Dick, a professor at UT Austin who researches railroad energy technologies. “But, like everyone else, there’s this incentive to try and further reduce the energy consumption and associated emissions with them.”

Wabtec aims to retrofit existing engines to use a blend of diesel and hydrogen fuel, which Chief Technology Officer Eric Gerbhardt says would reduce the carbon emissions by 80%. But the company says it will be several years until its first retrofitted locomotive is commercially available and at least 2030 before the economics of hydrogen make sense for a broader rollout.

Availability of clean hydrogen

Locomotives last between 30 to 40 years, and rail companies aren’t inclined to swap in new versions of the expensive equipment early. By modifying the existing locomotives to use hydrogen, Wabtec hopes to speed up the adoption of alternative fuels.

“It gives optionality, because our hypothesis is that these fuels are not going to be available everywhere all at once,” Gebhardt says.

Indeed, availability is a key concern. Approximately 10 billion kilograms of hydrogen is produced in the U.S. every year—the equivalent of 10 billion gallons of fuel. Powering U.S. freight rail required 3.1 billion gallons of fuel in 2022. However, trucks—a potential competitor for hydrogen fuel—used 172 billion gallons of fuel that same year. In other words, the amount of hydrogen currently being produced in the U.S. is a drop in the bucket of what would ultimately be needed.

The federal government is trying to help solve this issue. As a part of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, $8 billion was earmarked for hydrogen hubs across the country.

There’s also the fact that hydrogen isn’t necessarily a clean fuel. While it produces no carbon dioxide, it requires a lot of electricity to produce—and that energy can come from clean or dirty sources.

“In some cases, depending on where that electricity is coming from, you are actually creating more emissions than if you just had a diesel engine on the locomotive providing that power,” Dick said.

Green hydrogen is rare at the moment (95% is made using natural gas, which comes with significant emissions), but as production scales up, that could change.

Hydrogen also presents safety challenges, as it’s a very small, very flammable molecule prone to finding its way through cracks in storage containers. Dick says these containers would require a cryogenic component to keep the hydrogen at a low enough temperature to maintain its density. Wabtec plans to have a car behind the locomotive that would carry the hydrogen at a low temperature.

Lowering Rail Emissions

Regulators and shippers seeking to reduce carbon emissions have pushed the industry to clean up its operation. Last year, for example, California passed regulations requiring all freight rail locomotives built after 2035 to be zero-emission.

Right now, the vast majority of freight and passenger rail operations in the U.S. are powered by diesel. In addition to hydrogen, companies are looking at a range of alternatives, including battery, overhead electric, renewable diesel, and biodiesel.

While Dick says overhead electric would be three to four times more efficient than using electricity to produce hydrogen, it would require a massive investment to update rail infrastructure across the country. Wabtec says the lack of infrastructure is why it’s not currently investing in electric freight trains.

A transition from diesel to hydrogen fuel offers some unique advantages, Dick said. The actual process of fueling is similar. With a diesel engine, the train pulls into the station, and fills up its 5,000 gallon tank with a hose in 20 to 30 minutes, Dick said. The process with hydrogen would be similar—albeit with a molecule that’s more of a compressed gas. That said, it takes much more time. If a locomotive were running on 100% hydrogen, it would take 6.5 hours to refuel, although Wabtec hopes to significantly reduce that in the next few years.

Wabtec also plans to launch engines that can use 20% biodiesel and 100% renewable diesel later this year, which Gebhardt said would reduce carbon emissions from the engine by 60%. (Although there are still broader questions about their emissions.)

Diversifying Rail

There are already some examples of non-diesel rail operations in the U.S. For example, the short haul Pacific Harbor Line in the Los Angeles area uses battery powered locomotives. The Florida East Coast Railway is using Wabtec locomotives powered by a blend of diesel and liquid natural gas—a similar technology to its blended diesel and hydrogen engine.

Europe has made greater strides toward a cleaner rail operation, which Dick attributes partially to the continent’s climate goals. Lighter European freight trains largely use electric overhead wires and are more nimble so they can operate on a rail network that caters to passenger rail.

In the U.S., passenger rail is also exploring alternative energy. A train in San Bernardino, California is aiming to be the first hydrogen-powered, zero-emission passenger train in North America next year.

Dick doesn’t expect a dramatic, overnight change. Things move slowly in the freight rail industry. However, he believes there’s too much momentum behind alternative energy for there not to be advancements in the coming years.

“If the regulations continue, if there continues to be this pressure from shippers and the public pushing toward certain climate goals . . . then you’ll gradually see these technologies gain momentum and gain a foothold within the railroad industry,” he says. “I think it’s inevitable that there will be some change.”