Why laptop makers keep trying wild new ideas

Every year, laptops get faster and more power-efficient. And over the decades, their average thickness has decreased as chunky connectors and components have dwindled. But despite the many functional improvements and refinements the laptop has undergone in the past 40 years, a time traveler from the 1980s would immediately recognize the best-selling laptop models today as computers due to their clamshell design. Its two decks—one focused on input, the other on display, foldable into a hinged stack—have long provided portable computers with protection and convenience, even if they have fallen short on ergonomics. The gravitational pull of the clamshell has proven so strong that Apple, for example, hasn’t strayed far from it since its first PowerBooks more than 30 years ago. Instead of messing with the MacBook’s clamshell form factor, Apple introduced the iPad Pro, a tablet with a laptop-size screen. Microsoft, whose 2-in-1 Surface devices launched as new spins on the mobile PC, eventually launched more traditional laptops. Its Surface Book, which introduced a novel hinge to let you detach the screen and use it like a tablet, gave way to the more conservative design of the Surface Laptop Studio, which operates in a traditional clamshell mode. And among Microsoft’s smaller-screen PCs, its entry-level Surface Laptop Go has outpaced its earlier entry-level 2-in-1 Surface Go tablet. Even the PC industry’s most successful variation on the standard clamshell—the 2-in-1 convertible with a 360-degree hinge—commands a small (albeit premium) slice of the market. Given the investment required and high risk in launching something that may lack staying power or even become a one-hit revenue engine, why do manufacturers keep pushing the boundaries of the traditional clamshell with new form factors? According to marketing and design leaders at major PC manufacturers, the benefits can include enjoying a halo effect, reaching out to new customer bases (especially Apple’s), and gaining feedback on design elements or features that may show up in more mainstream designs. Build versus ballyhoo When stretching the concept of how a PC looks or functions, executives agree that there’s no substitute for the learning that comes from discussing new ideas with distribution partners and getting them into customers’ hands, particularly among a targeted group of buyers. Eric Ackerman, senior product marketing and brand manager for Acer America, notes that positive reactions can extend well beyond a more experimental device. “I think the halo effect is very important for awareness and to lift brand perception. It’s kind of its own marketing to some degree. It also emboldens the team to try new things. Obviously, we want to be well thought out in our plan and implementation of anything new, but it definitely gives us some confidence.” As an example, he cites Acer’s Predator 21 X, a gaming “laptop” with a curved 21-inch display that the company offered in 2017 for $9,000. “We weren’t going to sell tens of thousands of those,” he says. “It had two GPUs, the 21-inch screen, a mechanical keyboard, all kinds of things going on. But man, did it get interest.’” Acer’s humongous Predator 21 X gaming laptop cost $9,000—and came with its own custom Pelican case. [Photo: Acer] Not all industrial design work is so obvious from the outside. Stacy Wolff, global head of design and sustainability at HP, also notes the value of shipping advanced products rather than just showing off concept design. He refers to HP’s enterprise-focused EliteBook line that allows easy access to repairs or upgrades for many core components that other companies have made difficult or impossible to service. This helps prolong the laptops’ usage and avoid e-waste. While PC startup Framework has been selling laptops that offer even more component modularity, Wolff notes that doing so at HP’s scale involves even more challenges, and the potential for greater impact. Lenovo has been particularly aggressive when it has come to exploring new form factors. The company has pioneered 2-in-1 wraparound convertible designs and offered PCs with multiple OLED displays (the Yoga Book 9i) and a mix of OLED and e-paper (ThinkBook Plus Gen 4), a folding-screen laptop (ThinkPad X1 Fold), and a handheld gaming PC (Legion Go). Brian Leonard, VP of design innovation for Lenovo IDG’s PCs and Smart Devices, relishes the experimentation. “We do spend a lot of time on new form factors,” he says. “Releasing a concept is really only about 5% of the work. Real hard work happens in getting it to production and going through all the issues and engaging in both a hardware and a software standpoint.” The long game For PC makers, a longer-term incentive for continuing to release experimental machines is the opportunity to refine technologies that will contribute to more successful products. Decades before the iPhone realized the vision of a pocket computer (and even dating back to the HP 95LX DOS

Every year, laptops get faster and more power-efficient. And over the decades, their average thickness has decreased as chunky connectors and components have dwindled.

But despite the many functional improvements and refinements the laptop has undergone in the past 40 years, a time traveler from the 1980s would immediately recognize the best-selling laptop models today as computers due to their clamshell design. Its two decks—one focused on input, the other on display, foldable into a hinged stack—have long provided portable computers with protection and convenience, even if they have fallen short on ergonomics.

The gravitational pull of the clamshell has proven so strong that Apple, for example, hasn’t strayed far from it since its first PowerBooks more than 30 years ago. Instead of messing with the MacBook’s clamshell form factor, Apple introduced the iPad Pro, a tablet with a laptop-size screen. Microsoft, whose 2-in-1 Surface devices launched as new spins on the mobile PC, eventually launched more traditional laptops. Its Surface Book, which introduced a novel hinge to let you detach the screen and use it like a tablet, gave way to the more conservative design of the Surface Laptop Studio, which operates in a traditional clamshell mode. And among Microsoft’s smaller-screen PCs, its entry-level Surface Laptop Go has outpaced its earlier entry-level 2-in-1 Surface Go tablet.

Even the PC industry’s most successful variation on the standard clamshell—the 2-in-1 convertible with a 360-degree hinge—commands a small (albeit premium) slice of the market.

Given the investment required and high risk in launching something that may lack staying power or even become a one-hit revenue engine, why do manufacturers keep pushing the boundaries of the traditional clamshell with new form factors? According to marketing and design leaders at major PC manufacturers, the benefits can include enjoying a halo effect, reaching out to new customer bases (especially Apple’s), and gaining feedback on design elements or features that may show up in more mainstream designs.

Build versus ballyhoo

When stretching the concept of how a PC looks or functions, executives agree that there’s no substitute for the learning that comes from discussing new ideas with distribution partners and getting them into customers’ hands, particularly among a targeted group of buyers.

Eric Ackerman, senior product marketing and brand manager for Acer America, notes that positive reactions can extend well beyond a more experimental device. “I think the halo effect is very important for awareness and to lift brand perception. It’s kind of its own marketing to some degree. It also emboldens the team to try new things. Obviously, we want to be well thought out in our plan and implementation of anything new, but it definitely gives us some confidence.”

As an example, he cites Acer’s Predator 21 X, a gaming “laptop” with a curved 21-inch display that the company offered in 2017 for $9,000. “We weren’t going to sell tens of thousands of those,” he says. “It had two GPUs, the 21-inch screen, a mechanical keyboard, all kinds of things going on. But man, did it get interest.’”

Not all industrial design work is so obvious from the outside. Stacy Wolff, global head of design and sustainability at HP, also notes the value of shipping advanced products rather than just showing off concept design. He refers to HP’s enterprise-focused EliteBook line that allows easy access to repairs or upgrades for many core components that other companies have made difficult or impossible to service. This helps prolong the laptops’ usage and avoid e-waste. While PC startup Framework has been selling laptops that offer even more component modularity, Wolff notes that doing so at HP’s scale involves even more challenges, and the potential for greater impact.

Lenovo has been particularly aggressive when it has come to exploring new form factors. The company has pioneered 2-in-1 wraparound convertible designs and offered PCs with multiple OLED displays (the Yoga Book 9i) and a mix of OLED and e-paper (ThinkBook Plus Gen 4), a folding-screen laptop (ThinkPad X1 Fold), and a handheld gaming PC (Legion Go). Brian Leonard, VP of design innovation for Lenovo IDG’s PCs and Smart Devices, relishes the experimentation. “We do spend a lot of time on new form factors,” he says. “Releasing a concept is really only about 5% of the work. Real hard work happens in getting it to production and going through all the issues and engaging in both a hardware and a software standpoint.”

The long game

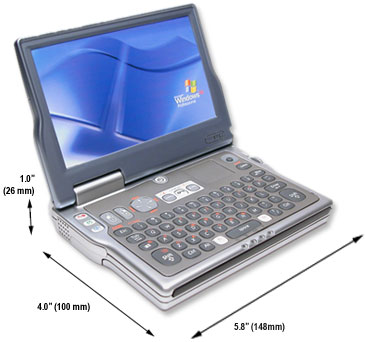

For PC makers, a longer-term incentive for continuing to release experimental machines is the opportunity to refine technologies that will contribute to more successful products. Decades before the iPhone realized the vision of a pocket computer (and even dating back to the HP 95LX DOS Palmtop in 1991), companies had tried to make PCs smaller, pushing limits of usability. Following the release of a few novel portable PCs in the early 2000s, Microsoft and Intel launched the Ultra Mobile PC initiative, It encouraged manufacturers to offer tiny Windows devices with screens ranging from about 5 inches to 9 inches, which was often too small to accommodate a touch-typable keyboard.

Companies pursuing this new PC frontier offered devices with side-mounted split keyboards (Samsung Q1), Psion PDA-style clamshells (Viliv and the Vulcan FlipStart), a chunky Blackberry-style monoblock (Tiqit) and slide-up keyboards (Sony and OQO, which claimed the Guinness World Record for the smallest Windows PC). Decades after their demise, PC vendors have again begun exploring small-screen devices with handheld gaming products, such as the Asus Rog Ally and Lenovo Legion Go. Most of these devices dispense with keyboards in a bid to compete with such devices as the Steam Deck and Nintendo Switch.

And while the market for Steam Deck-style PCs is in its early days, the quest for the pocketable PC shows the long-time arc that new form factors must sometimes traverse to make a dent in the marketplace. Sometimes, it’s a question of technology catching up, as modern, power-efficient processors make the idea of a handheld gaming PC experience far more viable than it was 20 years ago.

Eliminating—or at least subverting—the keyboard was also an indirect goal of the Tablet PC, a Windows XP-era push from Microsoft to control PCs via touch or stylus. While that initiative didn’t go far, it set a precedent for a new generation of 2-in-1 convertibles with 360-degree rotating displays encouraged by Windows 8 touchscreen focus. However, even these got off to a rough start as the smaller version of the pioneering Lenovo Yoga debuted with the doomed Windows RT operating system. It was followed by the first Microsoft Surface with a detachable keyboard, also based on Windows RT.

Now, however, with smartphone-style capacitive touchscreens being far more common and better support for touch and pen input in the Windows user interface, every major PC company offers rotating 2-in-1 convertibles and many offer Surface-style tablets with detachable keyboards.

Noting how the Yoga’s hinge focus differed from twisting and flipping hinges of earlier tablet PCs, Lenovo’s Leonard cites the market leadership advantage that being early to a form factor can bring. But he stresses the importance of continuing to invest as a new design attracts inevitable competition. One of Lenovo’s latest dual-screen PCs, the ThinkBook Plus Gen 4, offers both an OLED and e-ink display and returns to the twist hinge that Lenovo used on earlier tablet PCs.

“The timing of when you release these things is so important,” Leonard says, adding that he chided some younger members of his team for not knowing that the twist hinge had been used 15 years earlier. Meanwhile, a feature from one his favorites, the ThinkPad Plus Gen 3, which had an 8-inch display on the side of the keyboard deck suitable for memos, is back in the Yoga Book 9i.

Acer’s Ackerman points to lessons from machines such as the Aspire R7, a laptop early to implement the kind of pull-forward “easel” display now used in Microsoft’s Surface Laptop Studio. But in Acer’s implementation, the trackpad was placed behind the keyboard. Users had access to typing even when the screen was moved forward, but the design compromised the experience when the screen was moved back as a more traditional clamshell. Ackerman explains that there is tension between manufacturers, who often want to try something new to expand the market or establish a niche and users, who—outside of early adopters—want to use features they’re already familiar with.

“The feedback on those products, absolutely, 100% was influential in follow-on products,” Ackerman says. “You could argue that they just need time to adapt, and there’s some truth to that. But sometimes it’s just, ‘Nope, you’ve gone too far.’”

Big and broad

As laptops have become most people’s primary PC and even larger laptops are acceptably thin and light, design challenges have shifted from portability to productivity. Most recently, the bigger push has been toward more screen real estate, or at least the flexibility to access it on demand via foldable displays. HP became the most recent company to enter the field with the Spectre Foldable. At a price of about $5,000, it—like many new form factors leveraging leading-edge tech—isn’t poised to top the sales charts.

However, the product provided an opportunity for HP to differentiate beyond the hardware, developing software to blend new functionality with familiarity in the context of the company’s close Microsoft partnership. According to HP’s Wolff, HP used extensive field-testing to identify an opportunity to extend Windows 11’s Snap feature to help organize windows around the shifting dynamics of a folding display.

“It’s actually two screens that are now connected,” he explains. “The keyboard could move forward slightly, which meant that you actually had one-and-a-half screens. So we went back to Microsoft and said, ‘Hey, let’s work together on this. We need to write on top of your code [to achieve seamlessness].’ And they were accepting of that.”

Wolff also highlights the ethnographic research that went into designing a different kind of on-the-go PC made for consumers, the Envy Move. The $900 all-in-one desktop PC includes a battery good for four to five hours and a back pocket for storing the integrated keyboard/trackpad device when being toted around. While not nearly as portable or posable as a folding-screen laptop, the Move offers a larger-screen experience for a fraction of the price. HP observed trial users starting off with the device in a traditional place on a desk, but soon saw them moving it into their kitchen, onto the floor for yoga sessions, into treehouses, and even bathrooms.

“Without prompt, without instruction, they showed us the flexibility,” Wolff notes. “The term we used is ‘roam within the home.’”

The Envy Move is a rare clear break from the classic laptop mold, a move driven by its use case of transportability and content consumption around a home rather than the outside world. As vendors continue to experiment with foldable displays, multiple displays, and, in the case of Sightful’s Spacetop, displays confined to augmented reality eyewear, we may be in for a stream of new form factors. But unlike the classic clamshell PC design, whether any of them will pry us far from the notebooks we’ve flocked to for 40 years is far from an open-and-shut case.

A brief timeline of mobile PC form factor milestones

1977: IBM introduces a 55-pound “portable” computer, the suitcase-style 5100. In 1981, the Osborne 1 has a similar design, but uses a PC operating system and cuts the weight in half. In 1983, Compaq introduces the Portable, the first “IBM-compatible” portable. Like the Osborne 1 and 5100, it has to be plugged in.

1982: The Epson HX-20 becomes the first battery-powered “laptop” computer with top-mounted display for true on-the-go use.

1982: The GRiD Compass pioneers the clamshell form factor.

1989: The DOS-based GRiDPad becomes the first successful tablet computer.

1989: Poqet introduces the Poqet PC, an early subnotebook that has a touch-typable keyboard and can run on AA batteries.

1991: The first Apple PowerBooks integrate a trackball-pointing device beneath the keyboard. In 1994, Apple switches to the now-ubiquitous integrated trackpad in its PowerBook 500 series.1991: HP unveils the 95LX, a “palmtop” clamshell running DOS.

1993: IBM introduces the ThinkPad 701 with its Butterfly sliding keyboard that unfolds when you open the laptop’s case. King Jim revisits the concept in 2015 with the Portabook, sporting a splitting keyboard with halves that rotate 90 degrees.1993: HP releases the OmniBook 300, with a pop-out mouse on the right side.

2001: IBM’s ThinkPad TransNote is designed to lie flat and automatically record notes written on a paired paper pad.

2003: Microsoft’s Tablet PCs running Windows XP Tablet Edition launch from major PC companies. They’re slates or have displays that slide, rotate, or twist on specialized hinges.

2006: Microsoft and Intel announce the UMPC (Ultra Mobile PC) initiative to encourage devices that can fit in a coat pocket. Samsung, OQO, Sony, Viliv, UMID, and Fujitsu all release products.

2009: Lenovo releases the ThinkPad W700ds, which includes a secondary display that slides out from behind the primary one.

2010: Toshiba releases the limited-edition Libretto W100 with dual 7-inch screens. In 2011, Acer releases the Iconia Tab 6120 with dual 14-inch displays.

2012: Lenovo launches first Yoga models with 360-degree wraparound hinge.2012: Microsoft releases the first Surface device with kickstand and detachable keyboard accessory.

2013: Acer Aspire R7 features a pull-forward “easel” display.HP (Spectre Folio) and Microsoft (Surface Laptop Studio) later release notebook PCs with displays that can be pulled forward.

2016: Lenovo releases the first Yoga Book with a flat “Halo” keyboard, transitioning to a secondary e-paper display in 2018. It continues to ship ThinkBook Plus models that include secondary e-paper displays.

2017: Kangaroo, a brand owned by projector maker InFocus, releases a laptop shell for its mini-stick PC.

2020: Asus releases the first ZenBook Duo, which integrates a 12.7-inch touch display above the keyboard on the lower deck. Later models have raised its angle.

2021: Lenovo releases the ThinkPad X1 Fold, the first laptop with a folding screen.

2022: Valve releases the Steam Deck, a gaming handheld with a Nintendo Switch-like form factor. Asus and Lenovo are among the first major vendors to put Windows on such a device.

2023: Lenovo releases the Yoga Book 9i, which breaks out the keyboard to allow full use of two hinged OLED touchscreens.