Science just brought us one step closer to solving a billion-year-old mystery

We are fascinated by stories about the past. Every time I see a commercial for Ancestry.com I am reminded of the allure of where we as individuals came from. I am also drawn to stories about how the universe was created. Which is why the discovery of 80 new supernovae—the oldest ever identified, appearing a mere 1.9 billion years after the Big Bang—has captured the imaginations of so many. This finding—think of it as the Ancestry family tree of the universe—was made possible by the convergence of science and engineering. The collaboration of these disciplines enabled scientists from the Steward Observatory and the University of Arizona to analyze data from the James Webb Space Telescope Advanced Deep Extragalactic Survey (JADES) program. It was complex work, but the principle can be simply stated: Measuring transients—sources of radiation that appear or disappear each year—lets you actually “date” them. Supernovae are themselves transients, and the difference between the newly discovered ones and the ones we knew about is the equivalent of the time lapse between pre-teenage years and an 82-year-old. That is dramatic, and the significance of finding these early exploding stars is that they will better help us understand the early universe—getting us closer than we have ever been to understanding what happened at the beginning of it all. We do not have all the answers yet, but we thrillingly took a giant step closer through the JADES discovery, which filled a 13.7-billion-year gap in our understanding. I have no doubt that brilliant researchers will build on this, and in time we will unlock some of the many remaining questions we all have when we gaze at the midnight sky. And that is what I love about science. From our ancient times to today, it is the constant exploration of our universe by experimenting, collecting, and analyzing data always with the goal of getting closer to the truth on our natural world. It was just a few centuries ago, in 1608—a blip on the cosmic timeline—that Dutch eyeglass and instrument makers Hans Lippershey, Zacharias Janssen, and Jacob Metiusan invented the telescope. A few years later, Galileo took an optical leap forward, and is credited with being the first to point his scope upward. That same year, 1611, German mathematician Johann Kepler also looked at the night sky and devised his three laws of planetary motion, which turned observation into science. The progressive development of space exploration eventually allowed for instruments to actually be deployed in space, circumventing the blurring effect of our atmosphere. This is personal to me: In 1990, my friend, NASA Astronaut Kathy Sullivan and the rest of the Discovery’s crew deployed the Hubble Space Telescope in low earth orbit. For three-plus decades, this Hubble telescope, a creative collaboration between NASA and the European Space Agency, has been doing the work that led to the identification of the latest supernovae. Their technology provides us with fantastic data and images of universe, and you have probably seen them: The breathtaking image of the “Pillars of Creation” (located in the Eagle Nebula) was first captured in 1995 and later revisited with enhanced technology. It is one of the most recognized and inspiring images from Hubble. From interrogating the micro world to better understanding coronaviruses or exploring the macro world to learn what happened when it all began, science will forever remain our best tool to truth and understanding. The James Webb Space Telescope is just the latest apparatus in our human exploration toolkit. Moreover, unlike the narrow parameters of Galileo and the groundbreakers of the past, today’s world-finders have social media to share their work and inspire millions with the possibilities of science. There is a powerful force called the overview effect—a state of awe astronauts feel when looking down from space at our tiny, fragile planet. For me, the JADES program created the “underview effect.” Looking up at the heavens, we understand just what a small role we play in the cosmic scheme. This motivates us to both understand and appreciate more of the world we all share.

We are fascinated by stories about the past. Every time I see a commercial for Ancestry.com I am reminded of the allure of where we as individuals came from.

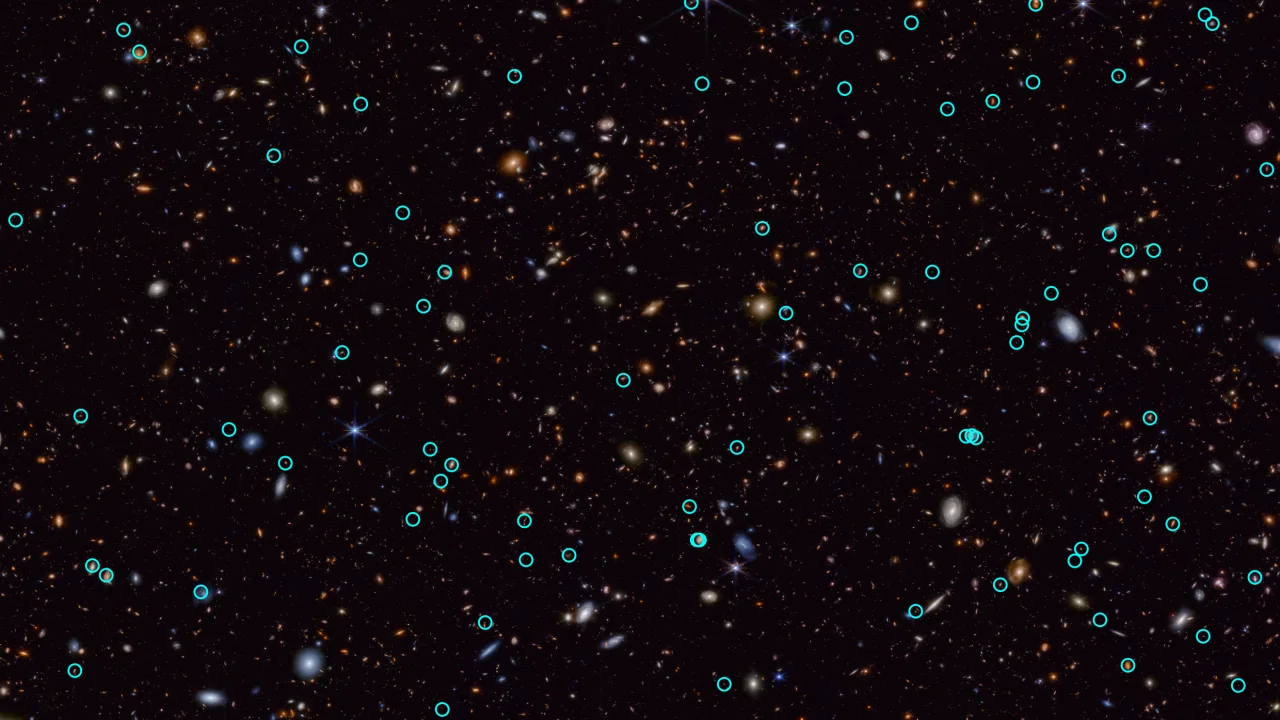

I am also drawn to stories about how the universe was created. Which is why the discovery of 80 new supernovae—the oldest ever identified, appearing a mere 1.9 billion years after the Big Bang—has captured the imaginations of so many.

This finding—think of it as the Ancestry family tree of the universe—was made possible by the convergence of science and engineering. The collaboration of these disciplines enabled scientists from the Steward Observatory and the University of Arizona to analyze data from the James Webb Space Telescope Advanced Deep Extragalactic Survey (JADES) program.

It was complex work, but the principle can be simply stated: Measuring transients—sources of radiation that appear or disappear each year—lets you actually “date” them. Supernovae are themselves transients, and the difference between the newly discovered ones and the ones we knew about is the equivalent of the time lapse between pre-teenage years and an 82-year-old.

That is dramatic, and the significance of finding these early exploding stars is that they will better help us understand the early universe—getting us closer than we have ever been to understanding what happened at the beginning of it all. We do not have all the answers yet, but we thrillingly took a giant step closer through the JADES discovery, which filled a 13.7-billion-year gap in our understanding.

I have no doubt that brilliant researchers will build on this, and in time we will unlock some of the many remaining questions we all have when we gaze at the midnight sky.

And that is what I love about science. From our ancient times to today, it is the constant exploration of our universe by experimenting, collecting, and analyzing data always with the goal of getting closer to the truth on our natural world. It was just a few centuries ago, in 1608—a blip on the cosmic timeline—that Dutch eyeglass and instrument makers Hans Lippershey, Zacharias Janssen, and Jacob Metiusan invented the telescope.

A few years later, Galileo took an optical leap forward, and is credited with being the first to point his scope upward. That same year, 1611, German mathematician Johann Kepler also looked at the night sky and devised his three laws of planetary motion, which turned observation into science.

The progressive development of space exploration eventually allowed for instruments to actually be deployed in space, circumventing the blurring effect of our atmosphere. This is personal to me: In 1990, my friend, NASA Astronaut Kathy Sullivan and the rest of the Discovery’s crew deployed the Hubble Space Telescope in low earth orbit.

For three-plus decades, this Hubble telescope, a creative collaboration between NASA and the European Space Agency, has been doing the work that led to the identification of the latest supernovae. Their technology provides us with fantastic data and images of universe, and you have probably seen them: The breathtaking image of the “Pillars of Creation” (located in the Eagle Nebula) was first captured in 1995 and later revisited with enhanced technology. It is one of the most recognized and inspiring images from Hubble.

From interrogating the micro world to better understanding coronaviruses or exploring the macro world to learn what happened when it all began, science will forever remain our best tool to truth and understanding. The James Webb Space Telescope is just the latest apparatus in our human exploration toolkit.

Moreover, unlike the narrow parameters of Galileo and the groundbreakers of the past, today’s world-finders have social media to share their work and inspire millions with the possibilities of science.

There is a powerful force called the overview effect—a state of awe astronauts feel when looking down from space at our tiny, fragile planet. For me, the JADES program created the “underview effect.” Looking up at the heavens, we understand just what a small role we play in the cosmic scheme. This motivates us to both understand and appreciate more of the world we all share.