Kind Humanoid wants to be the iPhone of cyborgs

It looks like a person made out of wires. Christoph Kohstall, founder of the startup Kind Humanoid, joins me on Zoom from his Palo Alto garage. He’s surrounded by computers, 3D printers, and a machine made for molding carbon fiber.Behind him hangs his company’s first prototype, an unskinned humanoid robot that could be your shame box of cords gone sentient. While it’s naked for now, a nearby 3D printer is creating a panel that will form its shell. Five years in development, in the middle of a $4 million funding round, Kind Humanoid wants to put a dozen of its robots into field testing next year, to be a generalist machine capable of assisting in areas facing labor shortages like healthcare—as part of a much larger race to be the defacto brand for humanoid robots we see between companies including Figure and Tesla.[Photo: Kind Humanoid]But while the system is a humanoid that stands on two legs and grasps things with two hands, it’s not designed to literally look human. Instead, the design firm Fuseproject was inspired by the 20th century surrealist Rene Magritte, who depicted people with objects obstructing their faces. Instead of a nose and mouth, the robot will feature a large visor that depicts animations of clouds and sky that almost resemble a desktop wallpaper. A pair of eyes float within this scenery to convey intent—morphing into eyebrows for a smile or a series of dots when it’s thinking.[Images: Kind Humanoid]“Logically, there’s this idea that eyes give a sense of intent, and it’s really where you get the mood and feeling of the robot,” says Yves Béhar, founder of Fuseproject. “And you can anticipate where they want to go, or whether it’s thinking, or how it’s about to react.”Building a humanoid robotPeople have dreamed about building humanoid machines since the year 100, and it’s probably fair to say people have been debating the merits of such a device for just as long. Why should a robot resemble a human in the first place?“I saw it as the ultimate machine we could create, because it really combines this extremely flexible locomotion—it can get anywhere and operate in any space—and also has the dexterity of hands being able to manipulate a lot of stuff,” says Kohstall. Since the world is already designed for humans, a robot that moves like a human could theoretically fit right in.[Photo: Kind Humanoid]But people are hard to recreate. From our brain to our musculature, we are a machine 4.5 billion years in the making. Kohstall argues—explaining the bet his whole company is riding upon—building the humanoid form of his robot is actually possible today because of the rise of LLMs and other new AI technology.Before AI, robots had to be programmed to complete every action in a precise sequence, which meant they couldn’t possibly respond to every situation the world could present them. They had to be designed in a utilitarian way, with a form that could master particular tasks on an assembly line but nowhere else. But because LLMs can deduce intent and come up with solutions more dynamically, they open up the feasibility of a robot that makes its way through the world more like a human. As such, Kohstall positions his bot as a “chatGPT that can also act.” An AI with real agency.“Suddenly you don’t need such a robust, precise robot arm anymore; you can build something more flexible and compliant,” he says. “If you build one versatile machine, it will replace what specialized machines did previously. We saw this with the iPhone.”[Image: Kind Humanoid]Designing a new style of cyborgBéhar has overseen all sorts of robotic projects in the past. His work has includes the child-tutor Moxie, which features a fully animated cartoon face, and ElliQ, a more abstract lamp-come-to-life built for seniors living in isolation.Suffice it to say, none of these robots has become as popular as some of his firm’s creations; FuseProject more or less invented the ubiquitous bluetooth speaker. But Béhar was won over by Kind Humanoid when he first visited the company’s garage. After saying he was thirsty, the robot looked around, found a bottle of water, and poured it into a glass. That demonstration, Kohstall’s go-to jaw-dropper, was a perfect summary of how an LLM-based robot could skip countless programming steps to just take the initiative and help someone out. And it was meant to tease all of the soft tasks this robot could feasibly help with: ranging from handling light household tasks, to offering physical assistance, to serving as a physician’s assistant in hospitals.Fuseproject took equity in the company to translate the skinless robot into a more realized, and friendly, design, capable of fitting into many different environments.[Image: Kind Humanoid]“Living with robots around us feels sterilized or surrealistic,” notes Béhar. “[A robot] os a mirror of our humanity. It accentuates our human traits, which separates us from machines.” Rather than denying this sensation, Fuseproject acknowledged it within the design. D

It looks like a person made out of wires. Christoph Kohstall, founder of the startup Kind Humanoid, joins me on Zoom from his Palo Alto garage. He’s surrounded by computers, 3D printers, and a machine made for molding carbon fiber.

Behind him hangs his company’s first prototype, an unskinned humanoid robot that could be your shame box of cords gone sentient. While it’s naked for now, a nearby 3D printer is creating a panel that will form its shell.

Five years in development, in the middle of a $4 million funding round, Kind Humanoid wants to put a dozen of its robots into field testing next year, to be a generalist machine capable of assisting in areas facing labor shortages like healthcare—as part of a much larger race to be the defacto brand for humanoid robots we see between companies including Figure and Tesla.

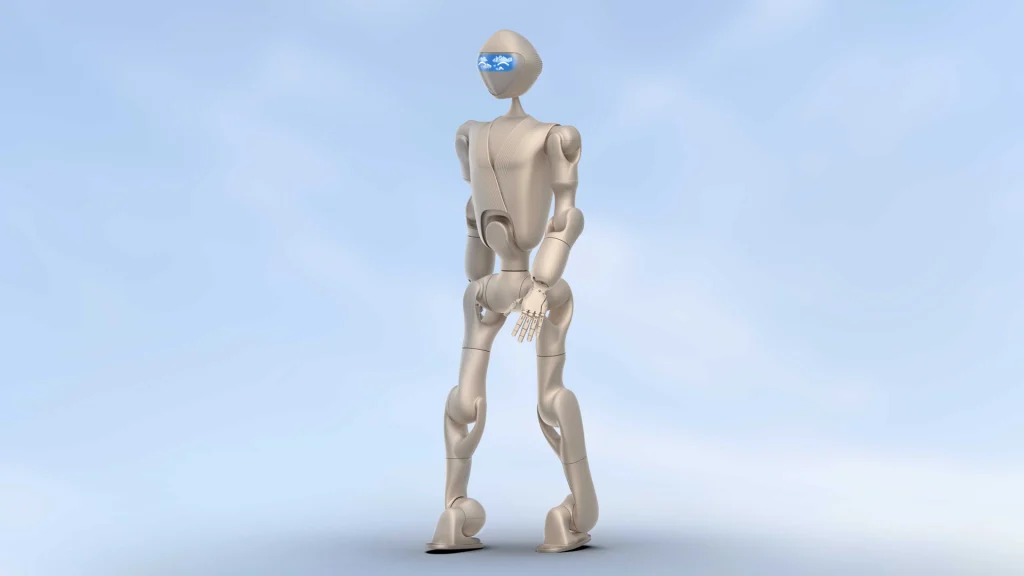

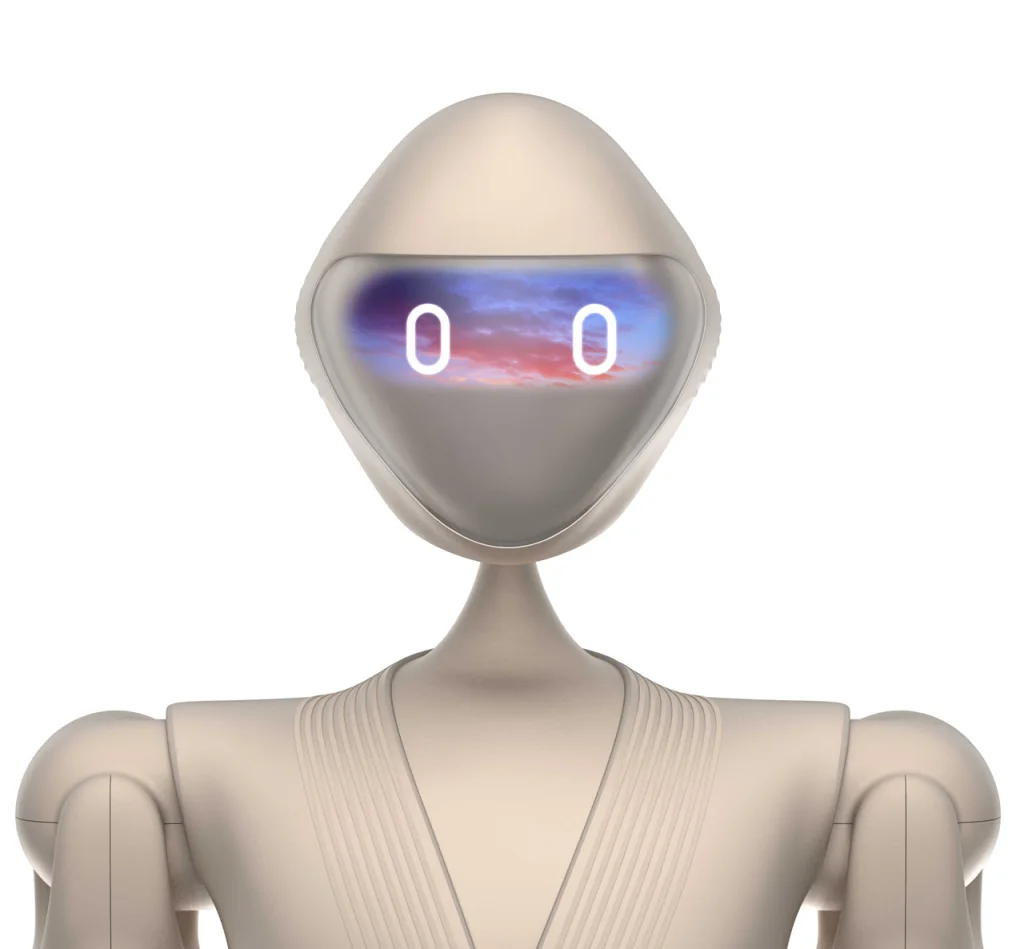

But while the system is a humanoid that stands on two legs and grasps things with two hands, it’s not designed to literally look human. Instead, the design firm Fuseproject was inspired by the 20th century surrealist Rene Magritte, who depicted people with objects obstructing their faces. Instead of a nose and mouth, the robot will feature a large visor that depicts animations of clouds and sky that almost resemble a desktop wallpaper. A pair of eyes float within this scenery to convey intent—morphing into eyebrows for a smile or a series of dots when it’s thinking.

“Logically, there’s this idea that eyes give a sense of intent, and it’s really where you get the mood and feeling of the robot,” says Yves Béhar, founder of Fuseproject. “And you can anticipate where they want to go, or whether it’s thinking, or how it’s about to react.”

Building a humanoid robot

People have dreamed about building humanoid machines since the year 100, and it’s probably fair to say people have been debating the merits of such a device for just as long. Why should a robot resemble a human in the first place?

“I saw it as the ultimate machine we could create, because it really combines this extremely flexible locomotion—it can get anywhere and operate in any space—and also has the dexterity of hands being able to manipulate a lot of stuff,” says Kohstall. Since the world is already designed for humans, a robot that moves like a human could theoretically fit right in.

But people are hard to recreate. From our brain to our musculature, we are a machine 4.5 billion years in the making. Kohstall argues—explaining the bet his whole company is riding upon—building the humanoid form of his robot is actually possible today because of the rise of LLMs and other new AI technology.

Before AI, robots had to be programmed to complete every action in a precise sequence, which meant they couldn’t possibly respond to every situation the world could present them. They had to be designed in a utilitarian way, with a form that could master particular tasks on an assembly line but nowhere else. But because LLMs can deduce intent and come up with solutions more dynamically, they open up the feasibility of a robot that makes its way through the world more like a human. As such, Kohstall positions his bot as a “chatGPT that can also act.” An AI with real agency.

“Suddenly you don’t need such a robust, precise robot arm anymore; you can build something more flexible and compliant,” he says. “If you build one versatile machine, it will replace what specialized machines did previously. We saw this with the iPhone.”

Designing a new style of cyborg

Béhar has overseen all sorts of robotic projects in the past. His work has includes the child-tutor Moxie, which features a fully animated cartoon face, and ElliQ, a more abstract lamp-come-to-life built for seniors living in isolation.

Suffice it to say, none of these robots has become as popular as some of his firm’s creations; FuseProject more or less invented the ubiquitous bluetooth speaker. But Béhar was won over by Kind Humanoid when he first visited the company’s garage. After saying he was thirsty, the robot looked around, found a bottle of water, and poured it into a glass. That demonstration, Kohstall’s go-to jaw-dropper, was a perfect summary of how an LLM-based robot could skip countless programming steps to just take the initiative and help someone out. And it was meant to tease all of the soft tasks this robot could feasibly help with: ranging from handling light household tasks, to offering physical assistance, to serving as a physician’s assistant in hospitals.

Fuseproject took equity in the company to translate the skinless robot into a more realized, and friendly, design, capable of fitting into many different environments.

“Living with robots around us feels sterilized or surrealistic,” notes Béhar. “[A robot] os a mirror of our humanity. It accentuates our human traits, which separates us from machines.”

Rather than denying this sensation, Fuseproject acknowledged it within the design. Designers referenced Magritte’s work with a screen instead of a green apple, which will animate more of a vibe than a face. This approach isn’t completely transparent, and some of its meaning might be found digging through Magritte’s own philosophy behind his work: “My painting is visible images which conceal nothing; they evoke mystery and, indeed, when one sees one of my pictures, one asks oneself this simple question, ‘What does that mean?’ It does not mean anything, because mystery means nothing, it is unknowable.”

In a sense, Béhar is channeling this ethos. He’s built an expressive language for the robot that is ultimately unknowable—and that’s, ironically, an earnest visualization of the lack of transparencies inside an AI’s logic. The robot is welcoming with a cloudscape or sunset, even if you don’t know what that scene means.

Building a bot’s body

As for the rest of the design, it’s full of both human and object references that are familiar but abstracted. The neck has an elegant, almost space-age taper, and back features striations that could be off a 1980s TV set that appear to double as venting. “We really spoke about the shape of the head, which we felt didn’t have to follow the oval shape of the human head,” says Béhar. “We felt it would create more character and uniqueness to have this soft diamond shape that seemed more expressive and unique.” And carefully, not exactly human.

The body is designed to be approachable, even touchable. As such, its skin isn’t white and black, like most robots, nor is it eerily flesh-toned either. Instead, it’s copper, what I’d call “robot flesh-tone.” It’s warm but mechanical. And then on the robot’s chest, you’ll note that skin looks like a kimono or jacket. The robot is clothed.

“We’re not trying to disguise the robot or give it a human appearance, but we do believe that we can make it softer in terms of the way it shows up,” says Béhar, “especially if we think of it in the hospital room, an age in place environment, the kitchen, and your backyard.”

I can appreciate that mission. But truth be told, I’ve been looking at these images for a week, and I still don’t know how I feel about Kind Humanoid’s design—in the same way I’ve never reconciled how I feel about Magritte’s own work. But what is clear is that, since the eyes are the window to the soul, Fuseproject gave a soulless object the equivalent of sunglasses.

“I feel like the Fuseproject team managed to make it this new type of creature, which is why this surrealistic reference hit it so well,” says Kohstall. “No, it’s not a human, but it can do all this stuff—so that feels surreal.”