Inside WeightWatchers’s fight to survive the Ozempic era

Sima Sistani’s relationship with WeightWatchers began like that of millions of other customers during the company’s six-decade reign as the world’s leading weight-loss brand. After the birth of her first child, in 2013, she had trouble shedding the 60 pounds she had gained during her pregnancy. She tried fad diets and cleanses. Then her mother, a registered dietitian, suggested she join WeightWatchers. Sistani did, and after getting acquainted with the company’s points system (every food is assigned a different value based on calories, sugar, protein, and fat), she began tracking her daily intake, always making sure to leave enough points for wine. The weight came off. Nearly a decade later, in 2022, Sistani became CEO of WeightWatchers (then called WW). At the time, the company—renowned for its in-person support groups—was wrestling with how to create a robust digital community in a Zoom-driven world. It was facing increasing competition from apps like Noom, which offers weight-loss support entirely online. Sistani had a reputation for understanding digital experiences: The former head of media at Tumblr, she had gone on to cofound and run the social networking app Houseparty, which she sold to Epic Games for $35 million in 2019. At the time of its acquisition, it had more than 150 million users. In announcing Sistani’s appointment as CEO of WeightWatchers, Raymond Debbane, then chair of the company’s board of directors, declared that “her vision and expertise in the digital, social, and gaming spaces perfectly position her to help lead us through this historic moment.” Except the challenge she ended up facing was completely different. The same month that Sistani became CEO of WeightWatchers, the FDA declared the first shortage of a drug that it had approved just a year prior: Wegovy, the semaglutide GLP-1 weight-loss medication made by Novo Nordisk. It was the proverbial sea receding ahead of the tsunami. A year later, Wegovy and Ozempic (Novo Nordisk’s other semaglutide drug, for type 2 diabetes, but widely used off-label for weight loss) made their red-carpet debut, with Academy Awards host Jimmy Kimmel surveying the assembled celebrities in the Dolby Theatre and evoking the TV ad lingo: “I can’t help but wonder, ‘Is Ozempic right for me?’” By the end of 2023, Novo Nordisk had notched more than $18 billion in annual sales of Ozempic and Wegovy, while sales of Eli Lilly’s rival GLP-1 drug, Mounjaro, surpassed $5 billion. GLP-1 sales are expected to hit $133 billion worldwide by 2030, according to MarketWatch. Where WeightWatchers once dominated the conversation around weight loss—with its emphasis on moderation and self-control, weigh-ins and calorie counting—it’s now struggling to keep up. In 2018, the company brought in $1.5 billion in revenue. It ended 2023 with annual revenue of $890 million, down 50% from its 2018 peak. The losses are mounting: On its most recent earnings call, WeightWatchers lowered its 2024 revenue outlook to at least $770 million, and said it could end the year with 3.1 million subscribers—which would be an 18% year-over-year drop. It’s now trimming costs and conducting layoffs, including executing a 40% reduction in employees at the VP level and above. WeightWatchers stock, which traded at more than $100 six years ago, is less than $1 a share. Sistani’s strategy hasn’t been to beat the drug-fueled wave in weight loss, but to accept it, and transform WeightWatchers into a healthcare provider that offers members access to medication as well as behavioral programs. She orchestrated the purchase, in spring 2023, of telehealth weight-management company Sequence for $132 million. Sequence, which was quickly rebranded as WeightWatchers Clinic, offers subscribers virtual access to physicians who can prescribe GLP-1 medication. Today, WeightWatchers still has its traditional meal-plan guidance and support-group programs, which account for roughly 90% of its revenue. But Sistani is banking on Clinic, which has more than 80,000 subscribers and costs $99 a month, to be a major engine for growth. WeightWatchers is now in the process of becoming a business—and a brand—that appeals to both weight-loss medication subscribers and dieters. “This is not just a transformation for our business; it’s a transformation for this category,” Sistani says. To succeed, WeightWatchers has to become a telehealth company, selling a wide swath of customers on drugs as the way to lose weight. And it needs to do it without alienating its traditional members, who still represent the bulk of its business. It’s a trick that might give even the strongest of companies pause. But WeightWatchers has no time to wait. Oprah Winfrey stood in a bright pink silk pantsuit on a stage in Midtown Manhattan in May. Speaking to the 100 or so women seated around her—and the many people who were streaming from home—she recalled one of the biggest regrets of her more than five-decade-long career in television

Sima Sistani’s relationship with WeightWatchers began like that of millions of other customers during the company’s six-decade reign as the world’s leading weight-loss brand. After the birth of her first child, in 2013, she had trouble shedding the 60 pounds she had gained during her pregnancy. She tried fad diets and cleanses. Then her mother, a registered dietitian, suggested she join WeightWatchers. Sistani did, and after getting acquainted with the company’s points system (every food is assigned a different value based on calories, sugar, protein, and fat), she began tracking her daily intake, always making sure to leave enough points for wine. The weight came off.

Nearly a decade later, in 2022, Sistani became CEO of WeightWatchers (then called WW). At the time, the company—renowned for its in-person support groups—was wrestling with how to create a robust digital community in a Zoom-driven world. It was facing increasing competition from apps like Noom, which offers weight-loss support entirely online. Sistani had a reputation for understanding digital experiences: The former head of media at Tumblr, she had gone on to cofound and run the social networking app Houseparty, which she sold to Epic Games for $35 million in 2019. At the time of its acquisition, it had more than 150 million users. In announcing Sistani’s appointment as CEO of WeightWatchers, Raymond Debbane, then chair of the company’s board of directors, declared that “her vision and expertise in the digital, social, and gaming spaces perfectly position her to help lead us through this historic moment.”

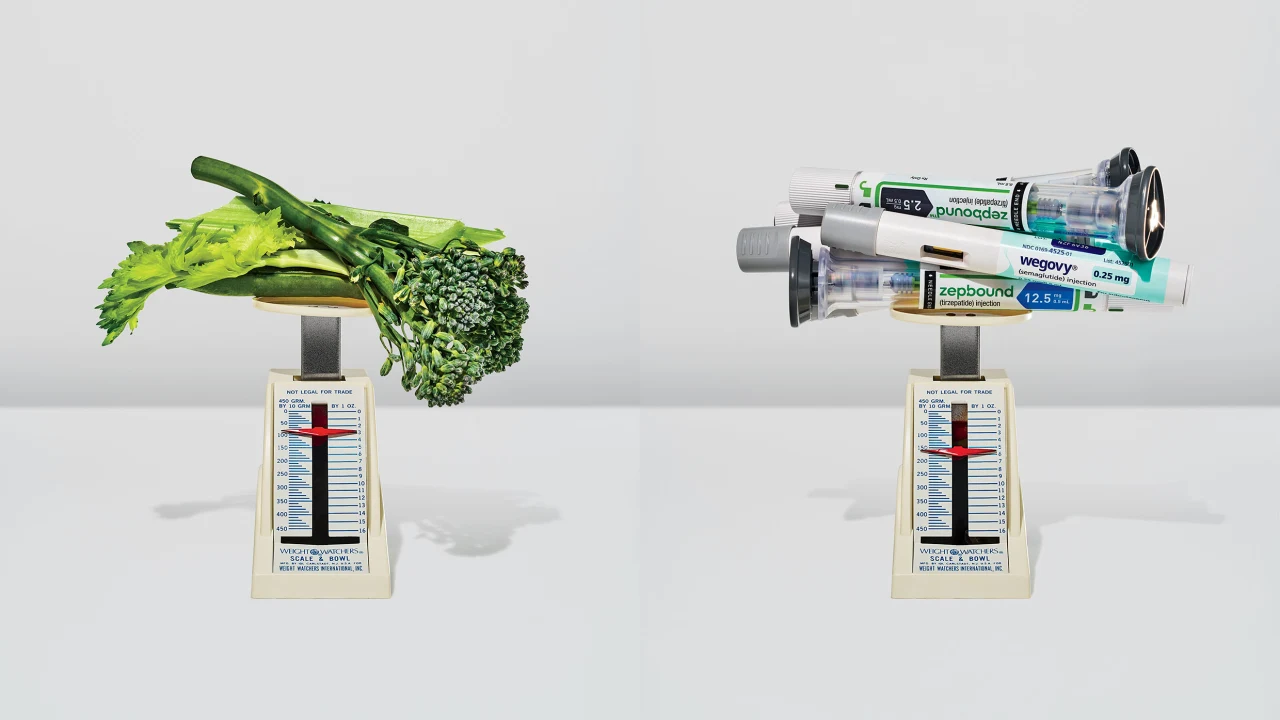

Except the challenge she ended up facing was completely different. The same month that Sistani became CEO of WeightWatchers, the FDA declared the first shortage of a drug that it had approved just a year prior: Wegovy, the semaglutide GLP-1 weight-loss medication made by Novo Nordisk. It was the proverbial sea receding ahead of the tsunami.

A year later, Wegovy and Ozempic (Novo Nordisk’s other semaglutide drug, for type 2 diabetes, but widely used off-label for weight loss) made their red-carpet debut, with Academy Awards host Jimmy Kimmel surveying the assembled celebrities in the Dolby Theatre and evoking the TV ad lingo: “I can’t help but wonder, ‘Is Ozempic right for me?’” By the end of 2023, Novo Nordisk had notched more than $18 billion in annual sales of Ozempic and Wegovy, while sales of Eli Lilly’s rival GLP-1 drug, Mounjaro, surpassed $5 billion. GLP-1 sales are expected to hit $133 billion worldwide by 2030, according to MarketWatch.

Where WeightWatchers once dominated the conversation around weight loss—with its emphasis on moderation and self-control, weigh-ins and calorie counting—it’s now struggling to keep up. In 2018, the company brought in $1.5 billion in revenue. It ended 2023 with annual revenue of $890 million, down 50% from its 2018 peak. The losses are mounting: On its most recent earnings call, WeightWatchers lowered its 2024 revenue outlook to at least $770 million, and said it could end the year with 3.1 million subscribers—which would be an 18% year-over-year drop. It’s now trimming costs and conducting layoffs, including executing a 40% reduction in employees at the VP level and above. WeightWatchers stock, which traded at more than $100 six years ago, is less than $1 a share.

Sistani’s strategy hasn’t been to beat the drug-fueled wave in weight loss, but to accept it, and transform WeightWatchers into a healthcare provider that offers members access to medication as well as behavioral programs. She orchestrated the purchase, in spring 2023, of telehealth weight-management company Sequence for $132 million. Sequence, which was quickly rebranded as WeightWatchers Clinic, offers subscribers virtual access to physicians who can prescribe GLP-1 medication. Today, WeightWatchers still has its traditional meal-plan guidance and support-group programs, which account for roughly 90% of its revenue. But Sistani is banking on Clinic, which has more than 80,000 subscribers and costs $99 a month, to be a major engine for growth.

WeightWatchers is now in the process of becoming a business—and a brand—that appeals to both weight-loss medication subscribers and dieters. “This is not just a transformation for our business; it’s a transformation for this category,” Sistani says. To succeed, WeightWatchers has to become a telehealth company, selling a wide swath of customers on drugs as the way to lose weight. And it needs to do it without alienating its traditional members, who still represent the bulk of its business. It’s a trick that might give even the strongest of companies pause. But WeightWatchers has no time to wait.

Oprah Winfrey stood in a bright pink silk pantsuit on a stage in Midtown Manhattan in May. Speaking to the 100 or so women seated around her—and the many people who were streaming from home—she recalled one of the biggest regrets of her more than five-decade-long career in television: the wagon of fat that she wheeled onto the stage of The Oprah Winfrey Show in 1988 to celebrate her 67-pound weight loss.

“I set a standard for people watching that neither I nor anybody else could uphold,” Winfrey recounted. “The very next day, I began to gain the weight back.” She wanted the audience, which included lifelong calorie counters and prominent body positivity influencers alike, to know that she was both a victim of toxic diet culture and complicit in it. “I have been a steadfast participant in this diet culture through my platforms, through [O] magazine, through the talk show for 25 years, and online.” Her cohost for the event, titled “Making the Shift,” was WeightWatchers.

For nearly a decade, Winfrey had been synonymous with WeightWatchers, touting the company’s self-control approach to weight loss in advertisements and even a national stadium tour. After taking a 10% stake in WeightWatchers in 2015, she served on its board and as its chief spokesperson. But after photos emerged last fall of her suddenly svelte figure, rumors that she was on weight-loss medication began swirling. She acknowledged taking the drugs in a December People cover story. A few months later, she aired an ABC special on the transformative power of weight-loss medications, including interviews with doctors who have received money from Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly. She also announced that she was divesting from WeightWatchers and stepping down from the board, effective May 2024. The announcement sent WeightWatchers stock tumbling by 25% in a single day in March. (Winfrey did not respond to an interview request for this story.)

The “Making the Shift” event was designed to reassure the markets that Winfrey wasn’t entirely distancing herself from the company. (Sistani says that Winfrey divested from WeightWatchers because “she didn’t want to be seen as profiting off clinical care” and was always planning to step away from the board.) It was also a way for WeightWatchers to reintroduce itself to audiences in its new form—as a destination for both behavioral and medical approaches to weight loss.

Sistani took the stage to explain this to the audience: “On our walls, it said, ‘It’s choice, not chance.’ That’s wrong.” She said that although WeightWatchers had helped millions of people over the years, the program “failed many people who walked away feeling that it was their moral failing, that it was their fault.” The message that Winfrey and Sistani kept repeating: We now know that obesity is a medical condition. “We did the best with the information that we had at the time, alongside every doctor and every scientific professional who was out there giving similar advice,” Sistani says.

WeightWatchers has been reckoning for years with its role in diet culture. In 2018, in response to the body positivity movement that had taken hold on social media and put the company on its back foot, WeightWatchers changed its name to WW, with the tagline “Wellness That Works.” The name change was mostly cosmetic. WeightWatchers’s program remained virtually unchanged. It was just now draped in health and wellness terms.

Executed under former CEO Mindy Grossman, the rebrand didn’t fool anyone. Instead, it threatened to eliminate the company’s core constituents, who still sought out the brand for weight loss, a phrase that WW seemed to avoid using. Then, when the pandemic hit, the company began shedding subscribers, while upstart digitally native companies like Noom gained market share. When Sistani took over, one of her first orders of business—in addition to building up the company’s digital platform—was to revert back to WeightWatchers.

If the body positivity movement eroded WeightWatchers’s business, the arrival of GLP-1s upended it. The company today is executing an ambitious brand pivot as it tries to pull its traditional behavioral offerings and its telehealth clinic under the same umbrella. To bring continuity to its business lines, it’s been combining support groups, placing traditional members with Clinic subscribers. The company has started giving Clinic subscribers diet plans, similar to what behavioral members receive, and it’s marketing its traditional programs to people on medication, whether or not they’re Clinic subscribers.

Sistani calls this the “one membership strategy,” which invites members to toggle between clinical and behavioral services, depending on their needs. As she sees it, even people on weight-loss medication need nutritional advice, and many don’t plan to stay on these drugs for life. Eventually they may rejoin the ranks of dieters.

WeightWatchers is also soliciting its traditional members to consider joining its Clinic program: More than half of them already meet the requirements for a GLP-1 prescription, a body mass index (BMI) of 30 or above, or a lower BMI with comorbidities like diabetes or cardiovascular conditions. Clinic’s largest customer segment today is current and former members of WeightWatchers’s traditional programs, according to chief product officer Donna Boyer. “The growth has been explosive,” she says. Even so, it may not be enough to compensate for the loss of subscribers on the behavioral side of the business.

The marketing of Clinic, meanwhile, is proving difficult. In February, WeightWatchers brought together a group of weight-loss influencers in a Los Angeles mansion (what it called the GLP-1 House) in hopes that they’d spend the day creating content: cooking nutritious meals while standing next to giant weight-loss drug syringes. The house, the company’s most prominent marketing effort for its Clinic subscription, faced a backlash on social media, with people calling out WeightWatchers for cashing in so quickly on weight-loss drugs.

As the company tries to embrace medication—and adjust to the cultural shift that it’s ushered in—WeightWatchers has been saddled by its reputation. “They are still selling weight loss as a solution,” says nutrition expert Christy Harrison, author of The Wellness Trap. “They seem critical of diet culture in some ways, but they still remain firmly rooted in diet culture.”

Sistani acknowledges the company’s struggle to square its Clinic business with its established brand. “We took some moves at the beginning to surround this conversation with joy, but trying to tell that story has been a hard one,” she says. “The biggest feedback we got from initial marketing was that it’s confusing. We live in this clickbait world now where everything needs to try to come across in 15 to 30 seconds, which is why our marketing is so difficult.”

WeightWatchers still appears to be figuring out its approach: It appointed Gut Miami as its agency of record last November, but the two parted ways just six months later. A marketing executive with knowledge of the company’s discussions with ad agencies says that despite WeightWatchers’s brand recognition, it would be almost easier to build and market a new GLP-1 prescription company from scratch.

Melissa Ressa first joined WeightWatchers while in college in 2010 after her mother, a member, recommended it. “My mom jokes that my first WeightWatchers meeting was when I was 6 months old and I was in a car seat next to her,” she says. After Ressa graduated, she got married, had kids, and regained the weight. She joined the service again, in 2021, this time connecting with a support group online. The points-based method worked, initially, and she lost 65 pounds. But then she hit a plateau. “From May 2023 until the end of November, I fought with my brain every single day. I was obsessing about food all the time,” she says. That’s when she decided to give WeightWatchers Clinic a shot.

She filled out a questionnaire and chatted with a physician asynchronously who provided her with a GLP-1 prescription. She started on Wegovy. “For the first time, I just ate to exist. It was life-changing,” she says. After three months on what she calls “the miracle drug,” however, she found that her insurance would no longer cover it, and she couldn’t afford the out-of-pocket expense. Wegovy currently costs around $1,300 a month out of pocket; Zepbound, Eli Lilly’s weight-loss drug, is $1,000.

[carousel_block id=”carousel-1725369796499″]After consulting with her WeightWatchers physician, Ressa’s now on Contrave, a less effective weight-loss drug. It’s fine for now, though she hopes GLP-1s will become more accessible to her soon.

Ressa’s experience with WeightWatchers Clinic is fairly common. Many Clinic subscribers are WeightWatchers members who have hit some sort of wall. Her story also highlights a major pain point for Clinic customers: Even if they pay the $99 monthly fee to access a physician and get a prescription, there’s no guarantee that their insurance will cover the medication—or that there will be enough supply in their area. (Wegovy and Zepbound have been cycling on and off the FDA shortage list.) “There’s so much demand for GLP-1 medications, and there’s not enough product for customers who are paying these monthly subscription fees,” says one former customer experience team member at WeightWatchers Clinic. “It just expanded way too fast.” On average, 8% of pharmacies have the right medication in stock for WeightWatchers members at any given time.

There are other hurdles facing WeightWatchers Clinic. Selling existing members access to GLP-1s is relatively easy; pulling in new customers is significantly harder. “Nearly everyone can figure out how to prescribe online, so it basically becomes a competition for which brands bid the highest to acquire customers [via ads] on Google or Meta,” says Sammi Inkinen, CEO of Virta Health, a competitor that offers weight-care programs to individuals and through employee benefit programs. WeightWatchers Clinic is also now competing with Noom, which began offering GLP-1 prescriptions in May 2023, and telemedicine companies like Ro, Calibrate, and Hims & Hers, which offer access to physicians who can prescribe drugs, including sometimes cheaper, compounded versions of GLP-1s.

Many insurance companies and employers are refusing to cover the medication due to its high price. Some are using techniques like raising the BMI cutoff, according to Rekha Kumar, chief medical officer of weight-loss company and WeightWatchers competitor Found. Sistani has touted her plans to expand Clinic as an employee benefit: More than 500 companies, after all, already offer their employees membership to WeightWatchers’s traditional program. But that ubiquity might not translate to Clinic. “It’s a tough sell to go [into employee benefit managers] and say, ‘We just acquired this company whose business is to maximize prescriptions.’ That’s not what a payer wants to hear,” says Virta Health’s Inkinen.

WeightWatchers is banking on GLP-1 prices dropping as supply ramps up, though it’s unclear when (or if) that will happen. To Sistani, it’s simply a matter of time. “When you look at the number of prescriptions that are written right now for Wegovy and Zepbound, it’s somewhere around a million,” she says. “If the market is growing, we’re growing alongside it.”

In the meantime, WeightWatchers continues to refine its approach to weight loss. Lately, executives have been talking about what they call “weight health.” The term can be a little vague. “It’s not about a certain size or a number on the scale. It’s about weight health. And that looks different for everyone,” reads one WeightWatchers web page. Sistani says she took inspiration from the rise of the term “mental health.” “If you think about somebody having depression or anxiety, it was [considered] a mental disease,” she says. “Calling it mental health let us put the focus back on the individual, and we started to embrace medical and pharmacotherapies in a way that didn’t create stigma and shame.”

The company that once helped to pathologize eating now wants to remove the shame of being overweight—for those who qualify for medication and can afford it. For everyone else, the traditional dieting program will have to do.