Harder than Harvard: How to get a job at the most in-demand tech companies

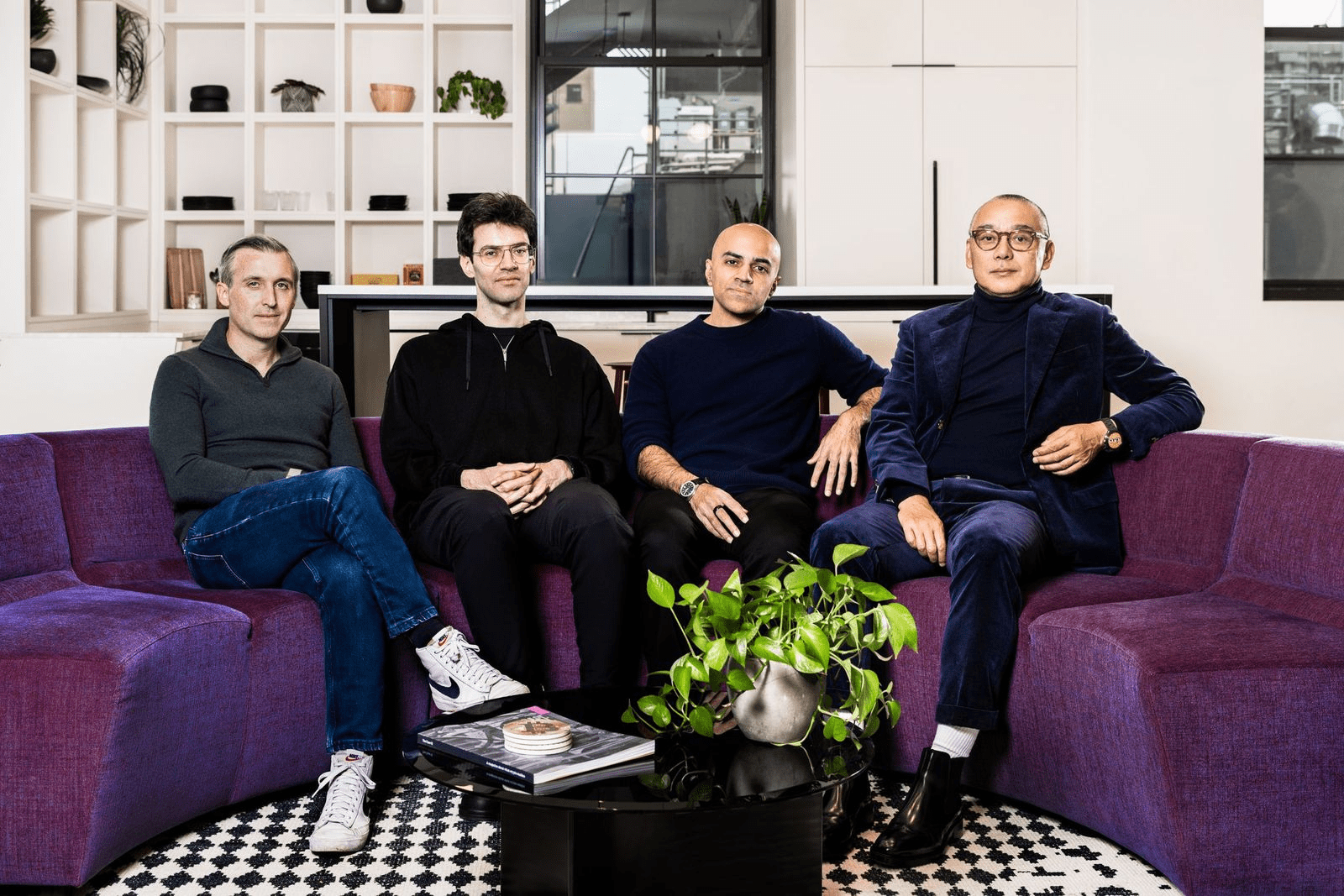

On December 1, podcaster and venture capitalist Harry Stebbings posted on LinkedIn that candidates were 200 times more likely to get into Harvard University than they were to get a job at the $6.6 billion valuation AI startup ElevenLabs. According to his statistic, out of 180,000 applicants in the first half of the year, only 0.018% were hired by the AI voice agent platform.

That figure—extrapolated from a July spike in applications—may have been hyperbole. But it still went viral. And out of tens of thousands of applications, just 132 candidates eventually got the job at ElevenLabs—indeed, much lower than Harvard’s 3% to 4% admission rates.

“On average, we’re seeing more people apply every quarter,” says Victoria Weller, VP of operations at ElevenLabs. “I hope that the high number of applicants motivates people—it’s inspiring to work somewhere that’s hard to get in. It’s like Harvard: once you’re in, you know you’re surrounded by the best people in an inspiring environment.”

In-demand companies are reinforcing their recruitment to cope with a volume of applications that often runs into the six figures. For example, ElevenLabs has tripled its recruitment team this year. Coinbase, which has a 0.1% hiring rate according to the company, has added AI tools to reach more candidates, surface stronger ones earlier, and support decision making.

The crypto exchange, which has a market cap of approximately $70 billion and is in the process of expanding into a financial superapp, has been long renowned for its stringent hiring process: candidates can expect six stages over 60 days—if they make it that far. And that was before a 2025 surge and a 45% year-over-year rise in applications, totaling in the hundreds of thousands.

“The size of the applicant pool doesn’t determine the quality of your hires—the rigor of your system does,” says Greg Garrison, VP, talent at Coinbase. “Our core process is largely the same, but the system has simply become more efficient and calibrated.”

Amid greater competition for fewer roles, and applications made easier than ever thanks to LinkedIn and generative AI, vacancies can receive hundreds—even thousands—of résumés within hours of going live. While this makes recruiters’ jobs harder, it also works in companies’ favor: high demand and low hiring signals prestige to the labor market; only the top 0.1% make the cut.

Beating the bots

Nicholas Bloom, professor of economics at Stanford University, believes companies’ eye-popping application numbers are largely bot-driven. “I know a Stanford undergrad that wrote code to apply to every job advert on a job board, and told me his friends use it too,” he says. “The big issue is this actually crowds out serious applicants. If you actually are in the 1% that applies by hand you have little chance of making it through.”

As a result of such intense demand, candidates can expect greater scrutiny—particularly at the earlier hiring stages.

In many cases, candidates will have to impress AI first. With a deluge of résumés in the inbox, ElevenLabs uses data-driven applicant tracking software Ashby to help sift the best candidates. “We have website fields asking applicants why they want to work with us and how our mission excites them,” says Weller. “That means you can identify who’s autofilled their details, and clicked ‘submit’ versus those that took the time to answer thoughtfully.”

It means quick-fire applications are unlikely to make it through to the next round: the screening call; the first round where candidates meet someone in the hiring position. So even when the acceptance rates are so tiny, ensuring to do the basics, like thoroughly answering questions—without the help of ChatGPT—could make a difference.

Beyond assessing candidates’ experience, the onus is on testing cultural fit. “There are certain types of questions that map to our values,” says Weller. “For example, we look for candidates with low egos, so we ask for feedback they’ve recently received—their answer can indicate their personality.” It means that the bragging LinkedIn posts aren’t perhaps a fair reflection of what hiring managers actually want from applicants.

While ElevenLabs has up to five assessment rounds in total, Coinbase candidates face the prospect of four interviews in a single stage—bookended by assessments and work trials before a potential offer is made. Experience—and persistence—separate the top 0.1% from the top 1%. “The best candidates tend to stand out,” says Garrison. “What separates them isn’t polish—it’s evidence. Their track record speaks louder than their résumé.”

But given the glut of applications, some of the best may slip through. Others might not even be seen at all.

Publicly posting near-zero acceptance rates is a marketing tactic, says Bloom. “Some companies love to flex on how hard it is to get a job with them. It’s a big show-off, just as colleges love tons of applications to flex on how low their yield rate is, so do some companies.”

Standing out from the crowd

Bots or not, with so many applications for the most coveted roles, it’s harder to get your résumé read by the right person.

That’s why networking becomes essential, says Mathew Schulz, founder of procurement newsletter Pennywurth. His own LinkedIn post comparing hiring rates at Ramp, the fintech that hit a $32 billion valuation last November, with Harvard admission rates—with just 0.23% of engineers hired—also went viral this year.

“It’s becoming even more difficult to submit your résumé and move along the process—a vacancy has hundreds of applicants within 24 hours of going live,” says Schulz. “So having a mutual connection, reaching out to contacts, and actively following up on LinkedIn becomes more important.”

With more top talent to choose from, companies can often afford to be pickier. Hiring managers are increasingly looking for candidates who are comfortable beyond their niche.

“More companies are looking for ‘builders’ and ‘creators’ who can do new things, are entrepreneurial-minded, and are highly skilled,” says Schulz. “There’s a lean towards being a generalist now versus a hyper-specialist.”

In practice, that can mean increasing a skillset, taking courses, and becoming adept at new tools that vacancies demand. “It’s like what they say: looking for a job becomes a full-time job,” says Schulz.

Getting through the door might be a bigger challenge than before. But once candidates are finally opposite a hiring manager, the fundamentals remain the same—no matter how low the acceptance rates.

“Good recruitment is still finding out, ‘What drives this person? What are they good at? Are they a good fit for the company?’” says Weller.

“That will always stay the same, regardless of what the process looks like.”