United Auto Workers tests its hold in the South as a Tennessee Volkswagen finishes voting on membership

The United Auto Workers’ ambitious drive to expand its reach to nonunion factories across the South and elsewhere faces a key test Friday night, when workers at a Volkswagen plant in Chattanooga, Tennessee, will finish voting on whether to join the union. The UAW’s ranks in the auto industry have dwindled over the years as foreign-based companies with nonunion U.S. plants have sold increasingly more vehicles. Twice in recent years, workers at the Chattanooga plant have rejected union membership. Most recently, they handed the UAW a narrow defeat in 2019 just as federal prosecutors were breaking up a bribery-and-embezzlement scandal at the union. But this time, the UAW is operating under new leadership, directly elected by its members for the first time and basking in a successful confrontation with Detroit’s major automakers. The union’s pugnacious new president, Shawn Fain, was elected on a platform of cleaning up after the scandal and turning more confrontational with automakers. An emboldened Fain, backed by President Joe Biden, led the union in a series of strikes last fall against Detroit’s automakers that resulted in lucrative new contracts. The new contracts raised union wages by a substantial one-third, arming Fain and his organizers with enticing new offers to present to workers at Volkswagen and other companies. “I’m very confident,” said Isaac Meadows, an assembly line worker in Chattanooga who helped lead the union organizing drive at the 3.8 million-square-foot (353,353-square-meter) plant, which manufactures Atlas SUVs and the ID.4 electric vehicles. “The excitement is really high right now. We’ve put a lot of work into it, a lot of face-to-face conversations with co-workers from our volunteer committee.” The UAW’s supporters have faced resistance from the company as well as from some Republican leaders. In a presentation this week apparently aimed at dissuading the plant’s 4,300 production workers from voting for the union, Volkswagen listed examples of how it pays and treats them well. And six Southern governors, including Tennessee’s Bill Lee, warned the workers in a joint statement last week that joining the UAW could cost them their jobs and threaten the region’s economic progress. Marick Masters, a business professor at Wayne State University in Detroit who studies the UAW, said there is a good chance that this election could bring the union a historic victory. Public opinion, Masters said, is now generally more aligned with unions than it was in the past. To approve membership, though, the workers in Chattanooga will have to look past the warnings that joining the union, with the accompanying higher wages, would lead to job losses. Since the UAW’s new contracts were signed in the fall with General Motors, Ford and Stellantis, all three companies have cut a relatively small number of factory positions. But Ford CEO Jim Farley has said that his company will have to rethink where it builds future vehicles because of the strike. “While the UAW’s reputation has improved as a result of new leadership and contracts, it’s still associated with a decline in the auto industry,” Masters said. Shortly after the Detroit contracts were ratified, Volkswagen and other nonunion companies handed their workers big pay raises. Fain characterized those wage increases as the “UAW bump” and asserted that they were intended to keep the union out of the plants. Last fall, Volkswagen raised production worker pay by 11%, lifting top base wages to $32.40 per hour, or just over $67,000 per year. The average production worker makes about $60,000 a year, excluding benefits and an attendance bonus. VW said its pay exceeds the median household income for the Chattanooga area, which was $54,480 last May, according to the U.S. Labor Department. But under the UAW contracts, top production workers at GM, for instance, now earn $36 an hour, or about $75,000 a year excluding benefits and profit sharing, which ranged from $10,400 at Ford to $13,860 at Stellantis this year. By the end of the contract in 2028, top-scale GM workers would make over $89,000. Zach Costello, a worker who trains new employees at the Volkswagen plant, said pay shouldn’t be benchmarked against typical wages in the Chattanooga area. “How about we decide what we’re worth, and we get paid what we’re worth?” he asked. VW asserts that its factories are safer than the industry average, based on data reported to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration. And the company contends that it considers workers’ preferences in scheduling. It noted that it recently agreed to change the day that third-shift workers start their week so that they have Fridays and Saturdays off. But Meadows, whose job involves preparing vehicles for the assembly line after the auto bodies are painted, said the company adds overtime or sends workers home early whenever it wants. “People are just kind of fed up with it,” he said.

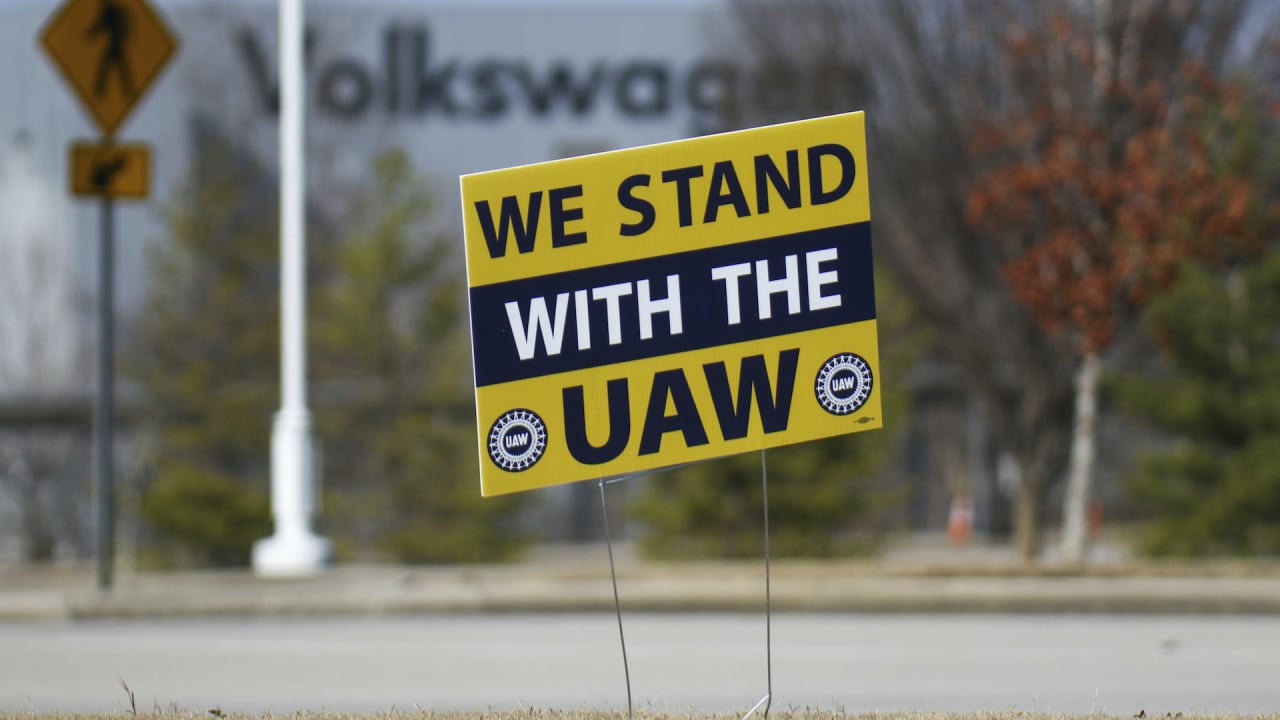

The United Auto Workers’ ambitious drive to expand its reach to nonunion factories across the South and elsewhere faces a key test Friday night, when workers at a Volkswagen plant in Chattanooga, Tennessee, will finish voting on whether to join the union.

The UAW’s ranks in the auto industry have dwindled over the years as foreign-based companies with nonunion U.S. plants have sold increasingly more vehicles.

Twice in recent years, workers at the Chattanooga plant have rejected union membership. Most recently, they handed the UAW a narrow defeat in 2019 just as federal prosecutors were breaking up a bribery-and-embezzlement scandal at the union.

But this time, the UAW is operating under new leadership, directly elected by its members for the first time and basking in a successful confrontation with Detroit’s major automakers. The union’s pugnacious new president, Shawn Fain, was elected on a platform of cleaning up after the scandal and turning more confrontational with automakers. An emboldened Fain, backed by President Joe Biden, led the union in a series of strikes last fall against Detroit’s automakers that resulted in lucrative new contracts.

The new contracts raised union wages by a substantial one-third, arming Fain and his organizers with enticing new offers to present to workers at Volkswagen and other companies.

“I’m very confident,” said Isaac Meadows, an assembly line worker in Chattanooga who helped lead the union organizing drive at the 3.8 million-square-foot (353,353-square-meter) plant, which manufactures Atlas SUVs and the ID.4 electric vehicles. “The excitement is really high right now. We’ve put a lot of work into it, a lot of face-to-face conversations with co-workers from our volunteer committee.”

The UAW’s supporters have faced resistance from the company as well as from some Republican leaders. In a presentation this week apparently aimed at dissuading the plant’s 4,300 production workers from voting for the union, Volkswagen listed examples of how it pays and treats them well. And six Southern governors, including Tennessee’s Bill Lee, warned the workers in a joint statement last week that joining the UAW could cost them their jobs and threaten the region’s economic progress.

Marick Masters, a business professor at Wayne State University in Detroit who studies the UAW, said there is a good chance that this election could bring the union a historic victory. Public opinion, Masters said, is now generally more aligned with unions than it was in the past.

To approve membership, though, the workers in Chattanooga will have to look past the warnings that joining the union, with the accompanying higher wages, would lead to job losses. Since the UAW’s new contracts were signed in the fall with General Motors, Ford and Stellantis, all three companies have cut a relatively small number of factory positions. But Ford CEO Jim Farley has said that his company will have to rethink where it builds future vehicles because of the strike.

“While the UAW’s reputation has improved as a result of new leadership and contracts, it’s still associated with a decline in the auto industry,” Masters said.

Shortly after the Detroit contracts were ratified, Volkswagen and other nonunion companies handed their workers big pay raises. Fain characterized those wage increases as the “UAW bump” and asserted that they were intended to keep the union out of the plants.

Last fall, Volkswagen raised production worker pay by 11%, lifting top base wages to $32.40 per hour, or just over $67,000 per year. The average production worker makes about $60,000 a year, excluding benefits and an attendance bonus. VW said its pay exceeds the median household income for the Chattanooga area, which was $54,480 last May, according to the U.S. Labor Department.

But under the UAW contracts, top production workers at GM, for instance, now earn $36 an hour, or about $75,000 a year excluding benefits and profit sharing, which ranged from $10,400 at Ford to $13,860 at Stellantis this year. By the end of the contract in 2028, top-scale GM workers would make over $89,000.

Zach Costello, a worker who trains new employees at the Volkswagen plant, said pay shouldn’t be benchmarked against typical wages in the Chattanooga area.

“How about we decide what we’re worth, and we get paid what we’re worth?” he asked.

VW asserts that its factories are safer than the industry average, based on data reported to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration. And the company contends that it considers workers’ preferences in scheduling. It noted that it recently agreed to change the day that third-shift workers start their week so that they have Fridays and Saturdays off.

But Meadows, whose job involves preparing vehicles for the assembly line after the auto bodies are painted, said the company adds overtime or sends workers home early whenever it wants.

“People are just kind of fed up with it,” he said.

VW, he argued, doesn’t report all injuries to the government, instead often blaming pre-existing conditions that a worker might have. The union has filed complaints of unfair labor practices, including allegations that the company barred workers from discussing unions during work time and restricted the distribution of union materials.

Volkswagen disputed the union’s allegations and said it properly reports injuries and supports the workers’ right to vote on union representation.

If the union prevails in the vote at the VW plant, it would mark the first time that the UAW has represented workers at a foreign-owned automaking plant in the South. It would not, however, be the first union auto assembly plant in the South. The UAW represents workers at two Ford assembly plants in Kentucky and two GM factories in Tennessee and Texas, as well as some heavy-truck manufacturing plants.

—Tom Krisher, Associated Press auto writer