This ingenious new period pad can screen you for deadly diseases

About two decades ago, a certain green-juice-loving tech mogul convinced the world that a single drop of blood processed inside an inscrutable black box dubbed Edison would be the revolution of diagnostics. But while Theranos was crashing and burning, another biotech company was building something a little different, and a lot more sensible. It involves your period. The Q-pad is an ingenious period pad that lets people who menstruate collect their menstrual blood from the comfort of their own home and get tested for a number of diseases like pre-diabetes and diabetes, thyroid health, anemia, fertility and perimenopause, and cervical cancer, which can currently only be detected through a fairly invasive pap test. It was approved by the FDA earlier this month, but not before going through over 1,000 design iterations (with the help of a menstruating robot named Betty.) Now, it’s on sale in the U.S. at a similar price point as a typical blood test ($49 for a pack of two.) The Q-pad is the brainchild of Dr. Sara Naseri and her biotechnology research company Qvin (pronounced kwin and derived from the word “woman” in Danish.) It works exactly like a regular period pad, except it also comes with a translucent oval that lets you know you’ve collected enough blood for diagnostic purposes, and a little tab that you pull to remove a paper strip. You then place the strip in a collection device before mailing it to your clinic, which can test it and share results on an app or via email. “We wanted to make sure that for women handling it, it was a simple and not a messy experience,” says Naseri. “You won’t see any dripping or anything like that.” [Image: Qvin] The Q-pad symbolizes a big step in the fight for sex equity in clinical research. Historically, women were often excluded or underrepresented in clinical trials in the United States. In 1977, the FDA banned most women of childbearing potential from Phase I and early Phase II drug trials. The policy was meant to safeguard women and their potential unborn children from potential risks linked to new medications, but its broad scope resulted in a lack of data on the impact of drugs on women—a challenge that still exists today. In 1986, NIH established a policy that encouraged researchers to include women in studies, but it wasn’t until 1993 that the policy became the law. “We are behind, quite frankly, on the knowledge that we have, and what is really upsetting is that even in conditions that primarily affect women, they are studied on male biology,” says Naseri, whose goal is to close the gender gap and give women an opportunity to not only understand what’s going on with their bodies but also be preventative about their healthcare. A eureka moment Naseri was still in med school when it dawned on her: women bleed every month, why has nobody used that blood for diagnostic purposes? “You’re bleeding anyway,” she told me. That was in 2013. At the time, there was only one paper she could find on the subject; it was published by a forensic department based on a murder case involving dried menstrual blood. But Naseri suspected there was clinical utility to menstrual blood, so she set out to prove it. She enrolled in Stanford University School of Medicine, founded Qvin in 2014, published her first paper in 2016, and proceeded to run more than 15 clinical trials. What she found was astonishing: menstrual blood has about 400 unique biomarkers. That is still less than half of the number of biomarkers found in veinous blood—as in the blood that comes from your veins. But as Naseri points out, that’s 400 markers we never knew existed in menstrual blood. Some of these biomarkers can also be found in veinous blood (in which case the Q-pad becomes a matter of convenience), but others are unique to menstrual blood. That’s the case for cervical cancer, which resides in the uterus, where blood flows through when a person is menstruating. In 2020, cervical cancer killed more than 340,000 women globally and Naseri says it’s only preventable if we screen for it. “It’s interesting because it really removes a barrier to access for healthcare when I don’t have to drive into the doctor’s office and get a poked with a needle,” she says. “I can, from the comfort of my own home, collect a blood sample that is a valid blood sample that can tell me information about my health.” Designing a new diagnostic process The Q-pad is the culmination of 10 years of research and about seven years of design iteration. Why so long? For one, women don’t menstruate all the time, and it can be hard to predict when that will happen. The high number of variables made it difficult for the team to iterate on the product, and inspired them to build Betty, a menstruating robot that Naseri jokily refers to as “a big member our of team.” Betty’s curious silhouette revolves around a pair of panties with a period pad strapped around a bicycle seat. One motorized arm pushes down on

About two decades ago, a certain green-juice-loving tech mogul convinced the world that a single drop of blood processed inside an inscrutable black box dubbed Edison would be the revolution of diagnostics. But while Theranos was crashing and burning, another biotech company was building something a little different, and a lot more sensible. It involves your period.

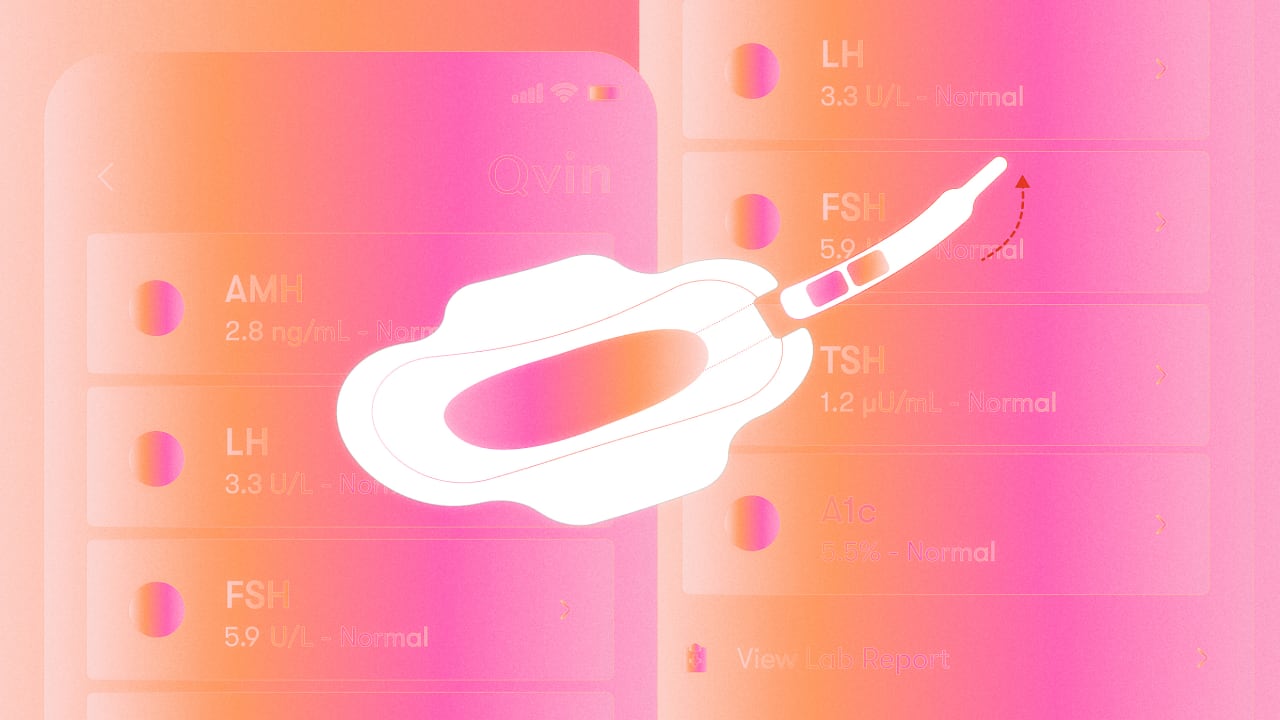

The Q-pad is an ingenious period pad that lets people who menstruate collect their menstrual blood from the comfort of their own home and get tested for a number of diseases like pre-diabetes and diabetes, thyroid health, anemia, fertility and perimenopause, and cervical cancer, which can currently only be detected through a fairly invasive pap test. It was approved by the FDA earlier this month, but not before going through over 1,000 design iterations (with the help of a menstruating robot named Betty.) Now, it’s on sale in the U.S. at a similar price point as a typical blood test ($49 for a pack of two.)

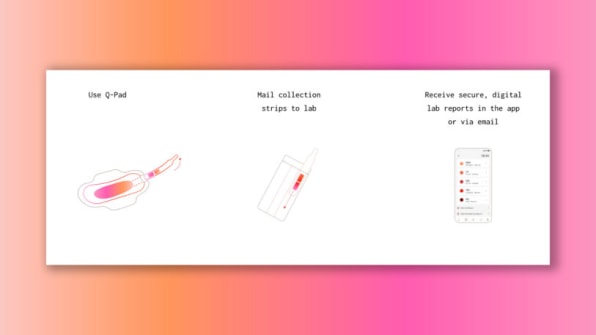

The Q-pad is the brainchild of Dr. Sara Naseri and her biotechnology research company Qvin (pronounced kwin and derived from the word “woman” in Danish.) It works exactly like a regular period pad, except it also comes with a translucent oval that lets you know you’ve collected enough blood for diagnostic purposes, and a little tab that you pull to remove a paper strip. You then place the strip in a collection device before mailing it to your clinic, which can test it and share results on an app or via email. “We wanted to make sure that for women handling it, it was a simple and not a messy experience,” says Naseri. “You won’t see any dripping or anything like that.”

The Q-pad symbolizes a big step in the fight for sex equity in clinical research. Historically, women were often excluded or underrepresented in clinical trials in the United States. In 1977, the FDA banned most women of childbearing potential from Phase I and early Phase II drug trials. The policy was meant to safeguard women and their potential unborn children from potential risks linked to new medications, but its broad scope resulted in a lack of data on the impact of drugs on women—a challenge that still exists today.

In 1986, NIH established a policy that encouraged researchers to include women in studies, but it wasn’t until 1993 that the policy became the law. “We are behind, quite frankly, on the knowledge that we have, and what is really upsetting is that even in conditions that primarily affect women, they are studied on male biology,” says Naseri, whose goal is to close the gender gap and give women an opportunity to not only understand what’s going on with their bodies but also be preventative about their healthcare.

A eureka moment

Naseri was still in med school when it dawned on her: women bleed every month, why has nobody used that blood for diagnostic purposes? “You’re bleeding anyway,” she told me.

That was in 2013. At the time, there was only one paper she could find on the subject; it was published by a forensic department based on a murder case involving dried menstrual blood. But Naseri suspected there was clinical utility to menstrual blood, so she set out to prove it. She enrolled in Stanford University School of Medicine, founded Qvin in 2014, published her first paper in 2016, and proceeded to run more than 15 clinical trials.

What she found was astonishing: menstrual blood has about 400 unique biomarkers. That is still less than half of the number of biomarkers found in veinous blood—as in the blood that comes from your veins. But as Naseri points out, that’s 400 markers we never knew existed in menstrual blood.

Some of these biomarkers can also be found in veinous blood (in which case the Q-pad becomes a matter of convenience), but others are unique to menstrual blood. That’s the case for cervical cancer, which resides in the uterus, where blood flows through when a person is menstruating.

In 2020, cervical cancer killed more than 340,000 women globally and Naseri says it’s only preventable if we screen for it. “It’s interesting because it really removes a barrier to access for healthcare when I don’t have to drive into the doctor’s office and get a poked with a needle,” she says. “I can, from the comfort of my own home, collect a blood sample that is a valid blood sample that can tell me information about my health.”

Designing a new diagnostic process

The Q-pad is the culmination of 10 years of research and about seven years of design iteration. Why so long? For one, women don’t menstruate all the time, and it can be hard to predict when that will happen. The high number of variables made it difficult for the team to iterate on the product, and inspired them to build Betty, a menstruating robot that Naseri jokily refers to as “a big member our of team.”

Betty’s curious silhouette revolves around a pair of panties with a period pad strapped around a bicycle seat. One motorized arm pushes down on the seat, while another tilts it back and forth to simulate various pressure types and flow rates. All of this happens while a long tube dispenses blood from a blood bag into the period pad—like the horror-movie version of an IV drip. Betty helped the team iterate until they found a reliable design that could collect blood regardless of the flow rate. Once that was solved, they started testing on real women. (No offense to Betty.)

Naseri says she tried “every modality” of blood period collection, including menstrual cups, but eventually settled on the period pad because people who menstruate are already familiar with the experience of it. A pad also maintains the integrity of the blood in a way a menstrual cup might not, in part because it comes with a surface area that is big enough for an integrated paper strip.

That’s not to say Qvin will stop at pads. “I do think that the technology we’ve built could be used in other feminine hygiene products,” she says, citing several patents for other ways of collecting blood: “The Q-pad is the first, but maybe there will be a Q-pon.”