The CDC nixes its 5-day COVID isolation rule—treating it more like the flu

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention just announced one of the biggest overhauls to its COVID-19 isolation guidelines in years—one that ends the agency’s long-standing recommendation that people who test positive for COVID-19 stay isolated indoors for five days and instead feel free to venture out once they’re relatively symptom-free. The new guidance, which reports hinted at last month, suggests that if you have COVID-19 and can get through 24 hours without showing the telltale symptoms (and without having to self-medicate), it’s okay to leave the house. This is first time the agency, in the face of an ever-evolving coronavirus, has revised its isolation recommendations since late 2021, when the CDC cut the original 10-day isolation window for those who test positive down to 5 days. But in a broader sense, this episode highlights how public health policies evolve alongside public health threats like the coronavirus—and how society comes to live with a new class of pathogen. “Our goal here is to continue to protect those at risk for severe illness while also reassuring folks that these recommendation are simple, clear, easy to understand, and can be followed,” CDC director Dr. Mandy Cohen said at a press briefing. The CDC revisions come on the heels of a brutal respiratory virus season driven by a trifecta of COVID-19, influenza, and RSV. There were 135,073 emergency room visits tied to COVID-19, flu, and RSV (respiratory syncytial virus) in the week ending February 10, according to CDC respiratory virus surveillance data, down from the season’s peak to date of 283,256 emergency room visits in the week ending December 30, 2023. Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention COVID-19 infections, hospitalizations, and deaths have fallen from a peak of about 35,000 new weekly COVID-related hospital admissions at the beginning of the year to about 21,000 admissions in the week ending February 10, according to the latest available CDC data. That’s the lowest recorded mid-February COVID-related hospitalization number in the four years since the pandemic upended the world, down from a peak of nearly 70,000 new weekly admissions in February 2022 when the highly transmissible omicron variant first reared its head. The waning hospitalization numbers are likely a key factor in changes for isolation guidance as COVID-19 joins other seasonal viruses that tend to peak over the winter months. “I do think it’s appropriate and it’s something we’ve anticipated,” Amesh Adalja, an assistant professor at Johns Hopkins and infectious disease expert, recently told a Fox News D.C. affiliate. “We’re sort of collapsing all of our guidance for respiratory viruses into one big guidance. . . . We’re in a much better place with COVID than we ever really have been.” California and Oregon had already scaled back their own statewide isolation recommendations this month for asymptomatic COVID-19 cases, bucking the federal CDC guidelines. Adalja and other experts still note caution. COVID-19 is ultimately a more serious illness for some than the flu, and CDC data shows that infections can also peak during the summer months. That was the case with an omicron subvariant last July. Another omicron subvariant, known as JN.1, is now projected to make up more than 92% of all COVID-19 cases in the U.S. and could exceed 96% in the coming weeks. But the CDC has noted a growing disconnect between infections and ensuing hospitalizations or deaths. “COVID-19 infections are now causing severe disease less frequently than earlier in the pandemic. Infection levels measured using wastewater and test positivity, which capture both symptomatic and asymptomatic infections, are higher than the year before (currently estimated as being ~27% and ~17% higher, respectively). Wastewater viral levels, in particular, have increased rapidly over the last several weeks,” the agency reported in January, adding, “Measures of COVID-19-related illness requiring medical attention, such as emergency department visit rates, have also increased,” yet remained “21% lower than they were at the same time the year before. . . . The number of COVID-19 hospitalizations are 22% lower than observed the year before, and the percent of total deaths associated with COVID-19 are 38% lower.” The numbers have only improved since then. There’s also considerable nuance around when someone with COVID-19 is most infectious. Much depends on when you take a test in the first place, and which coronavirus subvariant you might have. As many as 30% of COVID-19 cases might present without symptoms at all, and the incubation period for the virus can range anywhere from 2 to 12 days. Ultimately, the combined unpredictability of evolving COVID-19 strains alongside available vaccines, treatments, and general public awareness for a once-in-a-century virus makes these sorts of changes to isolation guidance inevitable. Update, March 1, 2024: This article has been

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention just announced one of the biggest overhauls to its COVID-19 isolation guidelines in years—one that ends the agency’s long-standing recommendation that people who test positive for COVID-19 stay isolated indoors for five days and instead feel free to venture out once they’re relatively symptom-free. The new guidance, which reports hinted at last month, suggests that if you have COVID-19 and can get through 24 hours without showing the telltale symptoms (and without having to self-medicate), it’s okay to leave the house.

This is first time the agency, in the face of an ever-evolving coronavirus, has revised its isolation recommendations since late 2021, when the CDC cut the original 10-day isolation window for those who test positive down to 5 days. But in a broader sense, this episode highlights how public health policies evolve alongside public health threats like the coronavirus—and how society comes to live with a new class of pathogen.

“Our goal here is to continue to protect those at risk for severe illness while also reassuring folks that these recommendation are simple, clear, easy to understand, and can be followed,” CDC director Dr. Mandy Cohen said at a press briefing.

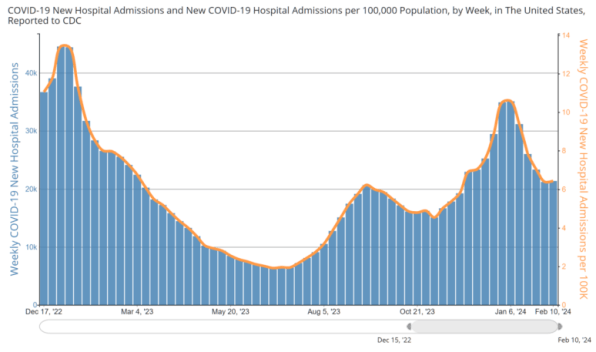

The CDC revisions come on the heels of a brutal respiratory virus season driven by a trifecta of COVID-19, influenza, and RSV. There were 135,073 emergency room visits tied to COVID-19, flu, and RSV (respiratory syncytial virus) in the week ending February 10, according to CDC respiratory virus surveillance data, down from the season’s peak to date of 283,256 emergency room visits in the week ending December 30, 2023.

COVID-19 infections, hospitalizations, and deaths have fallen from a peak of about 35,000 new weekly COVID-related hospital admissions at the beginning of the year to about 21,000 admissions in the week ending February 10, according to the latest available CDC data. That’s the lowest recorded mid-February COVID-related hospitalization number in the four years since the pandemic upended the world, down from a peak of nearly 70,000 new weekly admissions in February 2022 when the highly transmissible omicron variant first reared its head.

The waning hospitalization numbers are likely a key factor in changes for isolation guidance as COVID-19 joins other seasonal viruses that tend to peak over the winter months. “I do think it’s appropriate and it’s something we’ve anticipated,” Amesh Adalja, an assistant professor at Johns Hopkins and infectious disease expert, recently told a Fox News D.C. affiliate. “We’re sort of collapsing all of our guidance for respiratory viruses into one big guidance. . . . We’re in a much better place with COVID than we ever really have been.”

California and Oregon had already scaled back their own statewide isolation recommendations this month for asymptomatic COVID-19 cases, bucking the federal CDC guidelines.

Adalja and other experts still note caution. COVID-19 is ultimately a more serious illness for some than the flu, and CDC data shows that infections can also peak during the summer months. That was the case with an omicron subvariant last July. Another omicron subvariant, known as JN.1, is now projected to make up more than 92% of all COVID-19 cases in the U.S. and could exceed 96% in the coming weeks. But the CDC has noted a growing disconnect between infections and ensuing hospitalizations or deaths.

“COVID-19 infections are now causing severe disease less frequently than earlier in the pandemic. Infection levels measured using wastewater and test positivity, which capture both symptomatic and asymptomatic infections, are higher than the year before (currently estimated as being ~27% and ~17% higher, respectively). Wastewater viral levels, in particular, have increased rapidly over the last several weeks,” the agency reported in January, adding, “Measures of COVID-19-related illness requiring medical attention, such as emergency department visit rates, have also increased,” yet remained “21% lower than they were at the same time the year before. . . . The number of COVID-19 hospitalizations are 22% lower than observed the year before, and the percent of total deaths associated with COVID-19 are 38% lower.” The numbers have only improved since then.

There’s also considerable nuance around when someone with COVID-19 is most infectious. Much depends on when you take a test in the first place, and which coronavirus subvariant you might have. As many as 30% of COVID-19 cases might present without symptoms at all, and the incubation period for the virus can range anywhere from 2 to 12 days.

Ultimately, the combined unpredictability of evolving COVID-19 strains alongside available vaccines, treatments, and general public awareness for a once-in-a-century virus makes these sorts of changes to isolation guidance inevitable. Update, March 1, 2024: This article has been updated with the CDC’s official new guidance for COVID isolation.