Pax’s new vaping pod is made solely from pure cannabis. Is it any healthier?

Vaping has been a revolution for the cannabis industry, mostly due to the extreme convenience of getting high. Much like the iPod put thousands of songs into our pockets, the concentrated cannabis compounds in vape pens and their swappable, oil-filled pods offer 300-500 puffs in a tiny package. But then in 2019 we learned that vaping could lead to problems like popcorn lung. Suddenly, vaping cannabis has felt a lot like smoking cigarettes. Now Pax Labs, one of the earliest players in portable cannabis vaporizers, is debuting a product it designed to address the biggest concerns of vaping. Called Fresh Pressed Live Rosin pods, they are filled with nothing but cannabis compounds that have been cold-pressed almost like juice—with zero solvents or other chemical additives used in the process. Steven Jung, COO of Pax, compares these new pods to “raw food.” “Vapes as a category are definitely a race to the bottom,” says Jung. “We strategically don’t want to compete at that level.” [Photo: courtesy PAX] A brief history of modern vaping Pax Labs was originally founded in 2007 as a vaping company called Ploom. Focused on nicotine and cannabis, they made their mark by miniaturizing the large vaporizers popularized in the early aughts—like the Volcano—into something that would slide into a pocket. Vaporizers heat a leaf or an oil until it becomes vapor. Ideally, they do so at a low enough temperature that it never combusts, so that you don’t inhale carcinogens found in burning material. At Ploom, the divide between nicotine and cannabis resulted in two totally different business lines. It launched Juul, the infamous pod-baseds e-cigarette brand found to target children at the same time it was developing vape systems aimed at making the consumption of cannabis safer than smoking it. In 2017, Pax Labs spun off from Juul, and raised $420 million (heh). The companies are no longer related. [Photo: courtesy PAX]Pax Labs has spent the last few years attempting to help the cannabis industry evolve into something safer and more predictable. They sell both a whole leaf vaporizer called the Pax 3 that you pack with ground flower like a pipe, and a sleeker pod-based system called the Pax Era. With the Era, they’ve innovated by launching options like Session Control—basically, an electronic limiter you can put on how much you vape, so that you don’t get way too high—and single origin pods. You can think of single origin cannabis strains much like coffee beans. Most pods are a blend of THC extracted from any and all marijuana plants (a.k.a. your Starbucks Breakfast Blend). Pax tightened the supply chain behind their pods, allowing them to source single stains, more like drinking Yirgacheffe coffee from Ethiopia. (In this case, they offer Pineapple Express from California.) As Jung explains, the new Live Rosin pods are a continuation of their single origin work, to make a “cleaner and safer” pod with ingredients you can trace to the source. [Photo: courtesy PAX] Building a better pod The Live Rosin pods start with their industrial design. They’ve replaced the heating element, once fiberglass, with ceramic. That might sound like a forgettable detail, but inhaling heavy metals is one of the biggest risks to pods today, says Dr. Jordan Tishler, an instructor of medicine at Harvard, president of the Association of Cannabinoid Specialists, and a doctor who runs his own private practice. “These pens leach heavy metals from their heating cores into the [oil], and we inhale that,” says Tishler. The oil inside Pax’s new pods touches no metal. The only contact is with the ceramic heating element. (Tishler warns that any vape can still overheat and create carcinogens during combustion, but Pax-funded research has confirmed that the company’s temperature control technologies prevent this.) As for what it’s vaporizing? Pax has developed a proprietary process to ensure 100% of the contents of the pod are cannabis-based. Developing the oil inside most pods requires processes like butane and hexane extraction, each which involves heating the cannabis while adding chemical solvents to to help extract the THC. These solvents can be dangerous, according to Tishler, involving compounds like hydrocarbons that shouldn’t be inhaled. Pax’s approach is different, using nothing but water, ice, and pressure to do the job. While Jung declines to share all details for competitive reasons, it starts with the cannabis varietal being flash frozen. Then pressure/water extracts live rosin. Live rosin is a waxy cannabis concentrate that you can buy today, but dosing such a rich product can be tricky to do. [Photo: courtesy PAX]Then, Pax mixes the live rosin with two other cannabis extracts (sourced from a wider pool of plants than a single varietal): diamonds and terpenes. These liquid extracts thin out the waxy rosin to make the substance easily vapable. “It’s purely cannabis, from start to finish,” says Jung. There’s no diacetyl (the substance traced

Vaping has been a revolution for the cannabis industry, mostly due to the extreme convenience of getting high. Much like the iPod put thousands of songs into our pockets, the concentrated cannabis compounds in vape pens and their swappable, oil-filled pods offer 300-500 puffs in a tiny package. But then in 2019 we learned that vaping could lead to problems like popcorn lung. Suddenly, vaping cannabis has felt a lot like smoking cigarettes.

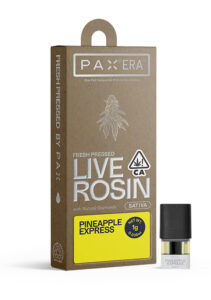

Now Pax Labs, one of the earliest players in portable cannabis vaporizers, is debuting a product it designed to address the biggest concerns of vaping. Called Fresh Pressed Live Rosin pods, they are filled with nothing but cannabis compounds that have been cold-pressed almost like juice—with zero solvents or other chemical additives used in the process. Steven Jung, COO of Pax, compares these new pods to “raw food.”

“Vapes as a category are definitely a race to the bottom,” says Jung. “We strategically don’t want to compete at that level.”

A brief history of modern vaping

Pax Labs was originally founded in 2007 as a vaping company called Ploom. Focused on nicotine and cannabis, they made their mark by miniaturizing the large vaporizers popularized in the early aughts—like the Volcano—into something that would slide into a pocket.

Vaporizers heat a leaf or an oil until it becomes vapor. Ideally, they do so at a low enough temperature that it never combusts, so that you don’t inhale carcinogens found in burning material.

At Ploom, the divide between nicotine and cannabis resulted in two totally different business lines. It launched Juul, the infamous pod-baseds e-cigarette brand found to target children at the same time it was developing vape systems aimed at making the consumption of cannabis safer than smoking it. In 2017, Pax Labs spun off from Juul, and raised $420 million (heh). The companies are no longer related.

With the Era, they’ve innovated by launching options like Session Control—basically, an electronic limiter you can put on how much you vape, so that you don’t get way too high—and single origin pods. You can think of single origin cannabis strains much like coffee beans. Most pods are a blend of THC extracted from any and all marijuana plants (a.k.a. your Starbucks Breakfast Blend). Pax tightened the supply chain behind their pods, allowing them to source single stains, more like drinking Yirgacheffe coffee from Ethiopia. (In this case, they offer Pineapple Express from California.)

As Jung explains, the new Live Rosin pods are a continuation of their single origin work, to make a “cleaner and safer” pod with ingredients you can trace to the source.

Building a better pod

The Live Rosin pods start with their industrial design. They’ve replaced the heating element, once fiberglass, with ceramic. That might sound like a forgettable detail, but inhaling heavy metals is one of the biggest risks to pods today, says Dr. Jordan Tishler, an instructor of medicine at Harvard, president of the Association of Cannabinoid Specialists, and a doctor who runs his own private practice.

The oil inside Pax’s new pods touches no metal. The only contact is with the ceramic heating element. (Tishler warns that any vape can still overheat and create carcinogens during combustion, but Pax-funded research has confirmed that the company’s temperature control technologies prevent this.)

As for what it’s vaporizing? Pax has developed a proprietary process to ensure 100% of the contents of the pod are cannabis-based. Developing the oil inside most pods requires processes like butane and hexane extraction, each which involves heating the cannabis while adding chemical solvents to to help extract the THC. These solvents can be dangerous, according to Tishler, involving compounds like hydrocarbons that shouldn’t be inhaled.

Pax’s approach is different, using nothing but water, ice, and pressure to do the job. While Jung declines to share all details for competitive reasons, it starts with the cannabis varietal being flash frozen. Then pressure/water extracts live rosin. Live rosin is a waxy cannabis concentrate that you can buy today, but dosing such a rich product can be tricky to do.

“It’s purely cannabis, from start to finish,” says Jung. There’s no diacetyl (the substance traced to popcorn lung) or ethylene/propylene glycol, both of which can become formaldehyde when heated. And not only does Pax argue their approach to pods is more natural; the company has developed a process that they can scale. Current laws require cannabis to be produced in the same state it is sold, which has made it hard for Pax to sell cannabis outside California. This new process can be set up in multiple states, according to Jung, allowing the company to sell to more of the U.S.

But are these new pods safe? Sharing the details with Tishler, he agrees that many of Pax’s developments seemed promising. “I admire Pax for continuing to try to develop safer products,” he says. “[But] I don’t think anybody in the vape pen space has hit it out of the park.”

His biggest lingering question around Pax’s new Live Rosin pod is regarding the addition of terpenes.

While a natural extract of cannabis, the amount of terpenes found in pods is disproportionately high compared to their appearance in nature—and we don’t know if there is a catch to their consumption. “We can say terpenes at the level we find in cannabis flowers seem to be safe, but we don’t know if it’s safe to inhale boatloads of it,” says Tishler.

There’s still a lot we don’t know about cannabis. As Tishler admits, he prescribes medical cannabis to patients, and recommends they avoid pods and instead vape flower at 350 degrees (or ingest it orally if that delayed timing, with longer lasting effects, can treat their symptoms). But he still doesn’t know that vaping flower is necessarily safer than smoking, because the scientific studies stating this don’t exist. It’s an assumption.

“What we have are studies that show smoking cannabis is not as harmful as smoking tobacco…and when you vape flower, you eliminate the smoke, so that’s [presumably] safer,” says Tishler.

What Tishler would like to see is independent testing of both vape devices and pods, to quantify the actual chemicals they are putting out during use. Pax claims to have done such work internally, but has not published their results. And no regulatory standard in cannabis vaping exists today.

Ultimately, Tishler believes pods are a promising technology that, in theory, could be safe for consuming cannabis if done right. Furthermore, he’s seen how much his own patients prefer the user experience of a pod over vaping flower. However, the realities of both science and regulation mean that it may be a long time until any doctor, scientist, or company can definitively make such a proclamation.

“Part of the problem is the studies on smoking take 20 years,” says Tishler. “We haven’t had these devices long enough.”