More people, more problems: Why growing coastal cities are vulnerable to climate disasters

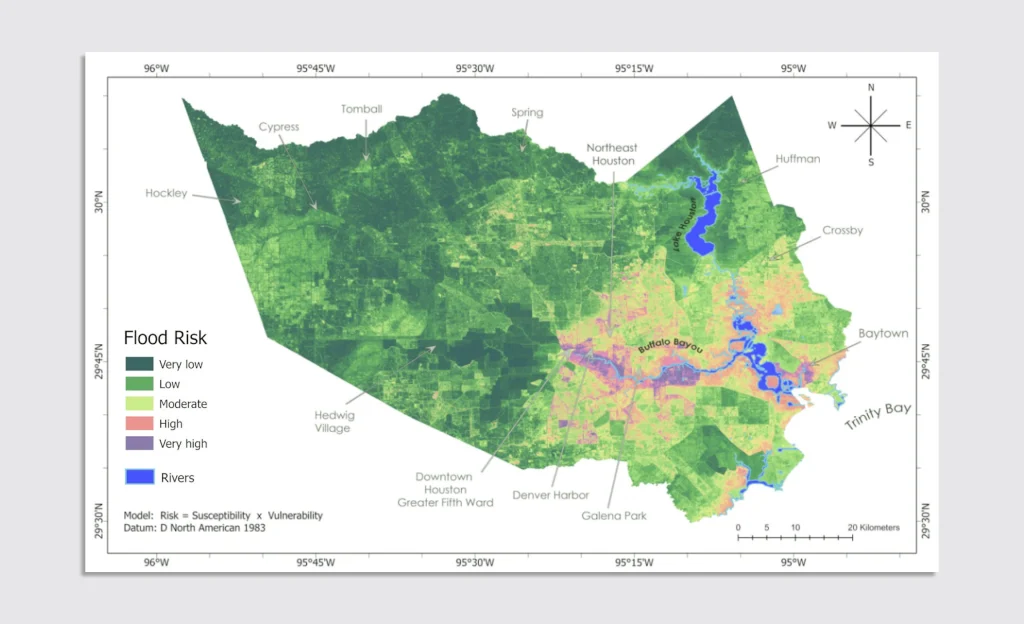

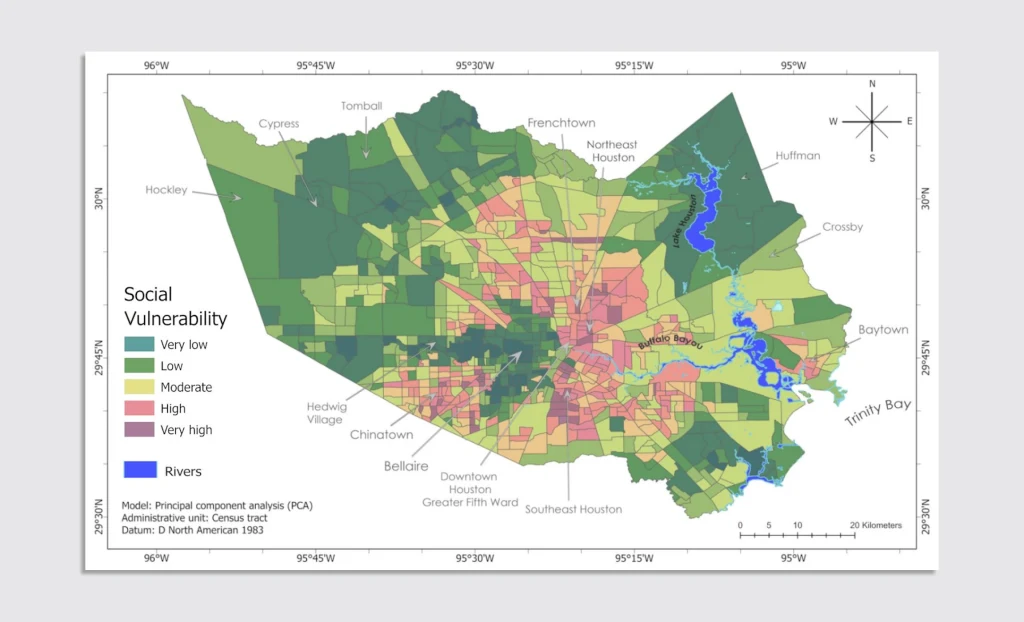

Warm water in the Atlantic Ocean and Gulf of Mexico can fuel powerful hurricanes, but how destructive a storm becomes isn’t just about the climate and weather—it also depends on the people and property in harm’s way. In many coastal cities, fast population growth has left more people living in areas at high risk of flooding. I am a geographer who studies the human dimensions of climate change and natural disasters. My research and mapping with colleagues shows that socially vulnerable communities—those least able to prepare for disasters or recover afterward—tend to be concentrated in areas that are more susceptible to flooding, particularly on the Gulf Coast. Larger, vulnerable populations Nearly 40% of the U.S. population lives in a coastal county today. Many of these areas are increasingly exposed to disasters, including hurricanes and high-tide flooding that has been worsened by sea level rise. The Gulf of Mexico region, in particular, is prone to climate change-induced concurrent disasters—when multiple disasters strike at once. For example, when Hurricane Beryl hit Texas in July 2024, 3 million homes and businesses lost power for several days in the middle of searing summer heat—in addition to dealing with heavy rain and flooding. To further complicate matters, more than one-fifth of the population in Harris County, home to Houston, is considered socially vulnerable, meaning people who are likely more susceptible to harm from extreme weather. New Orleans, another city with high social vulnerability, was under a hurricane watch and expecting power outages as Hurricane Francine headed for landfall in September 2024. Socially vulnerable populations in the U.S. include many older adults, people with disabilities, people living in poverty, mobile-home dwellers, and other marginalized groups. Often, they don’t have the resources or the physical ability to prepare for a storm, or the means to rebuild afterward. Several cities along the Gulf Coast—including Houston; New Orleans; Mobile, Alabama; and Tampa, Florida—have large socially vulnerable populations that are at high risk from hurricane damage. In many of these cities, patterns of land development and political decisions have elevated the potential for harm. A map of Houston shows the highest flood-risk areas. Hemal Dey/University of Alabama. First published in the Journal of Geovisualization and Spatial Analysis, 8, 19, 2024. [Image: Springer Nature, CC BY-ND] Houston’s social vulnerability map overlaps with the city’s highest flood-risk zones. Hemal Dey/University of Alabama. First published in the Journal of Geovisualization and Spatial Analysis, 8, 19, 2024 [Image: Springer Nature, CC BY-ND] Unbridled urban sprawl Houston offers a case study in the challenges created by unbridled urban sprawl in coastal cities. Harris County grew by one-third from 2000 to 2023, adding 1.3 million residents to become the third-most-populous county in the U.S. The economic boom accompanying that population growth brought jobs to the county, but not all of those jobs pay well. Harris County’s poverty rate is 16.5%, well above the national average of 11.5%. In the wake of Hurricane Harvey’s widespread flood damage in 2017, a heated debate ensued. Many observers pointed out a thorny reality: Houston was built on a swamp. The laissez-faire mentality typical of Texas politics that prioritizes not intervening in growth has further contributed to unbridled urban sprawl, turning wetland to concrete land. With wetlands simply paved over, heavy rain couldn’t be easily absorbed, making new neighborhoods extremely vulnerable to flooding. Preliminary research by my research group, which focuses on risk decision-making finds that, among all land use and land cover types in Harris County, developed land has increased fastest, rising from 35% of the county’s land in 2000 to 50% in 2020. Harvey was a vivid example of the importance of planning for storm water in urban development. Yet, as the storm’s devastation fades in the collective memory, more people are moving to Houston. With such high concentrations of people and infrastructure in the coastal region, more people are in harm’s way. More people means that when a disaster strikes, the impact can be much larger than it was just a few decades ago. Preparing for future disasters Coastal communities can’t afford to wait for a disaster’s wake-up call to invest in protecting themselves. To prepare for future disasters, I believe they need to rethink urban development with climate change in mind. Increasing resilience includes improving flood control infrastructure and enhancing emergency response capabilities with worsening storms in mind. It also involves adopting zoning rules that limit building in flood-prone areas. And it may even involve managed retreat—using buyouts to move some communities to safer ground. Public education campaigns are also important to raise awa

Warm water in the Atlantic Ocean and Gulf of Mexico can fuel powerful hurricanes, but how destructive a storm becomes isn’t just about the climate and weather—it also depends on the people and property in harm’s way.

In many coastal cities, fast population growth has left more people living in areas at high risk of flooding.

I am a geographer who studies the human dimensions of climate change and natural disasters. My research and mapping with colleagues shows that socially vulnerable communities—those least able to prepare for disasters or recover afterward—tend to be concentrated in areas that are more susceptible to flooding, particularly on the Gulf Coast.

Larger, vulnerable populations

Nearly 40% of the U.S. population lives in a coastal county today. Many of these areas are increasingly exposed to disasters, including hurricanes and high-tide flooding that has been worsened by sea level rise.

The Gulf of Mexico region, in particular, is prone to climate change-induced concurrent disasters—when multiple disasters strike at once. For example, when Hurricane Beryl hit Texas in July 2024, 3 million homes and businesses lost power for several days in the middle of searing summer heat—in addition to dealing with heavy rain and flooding.

To further complicate matters, more than one-fifth of the population in Harris County, home to Houston, is considered socially vulnerable, meaning people who are likely more susceptible to harm from extreme weather.

New Orleans, another city with high social vulnerability, was under a hurricane watch and expecting power outages as Hurricane Francine headed for landfall in September 2024.

Socially vulnerable populations in the U.S. include many older adults, people with disabilities, people living in poverty, mobile-home dwellers, and other marginalized groups. Often, they don’t have the resources or the physical ability to prepare for a storm, or the means to rebuild afterward.

Several cities along the Gulf Coast—including Houston; New Orleans; Mobile, Alabama; and Tampa, Florida—have large socially vulnerable populations that are at high risk from hurricane damage. In many of these cities, patterns of land development and political decisions have elevated the potential for harm.

Unbridled urban sprawl

Houston offers a case study in the challenges created by unbridled urban sprawl in coastal cities.

Harris County grew by one-third from 2000 to 2023, adding 1.3 million residents to become the third-most-populous county in the U.S. The economic boom accompanying that population growth brought jobs to the county, but not all of those jobs pay well. Harris County’s poverty rate is 16.5%, well above the national average of 11.5%.

In the wake of Hurricane Harvey’s widespread flood damage in 2017, a heated debate ensued. Many observers pointed out a thorny reality: Houston was built on a swamp. The laissez-faire mentality typical of Texas politics that prioritizes not intervening in growth has further contributed to unbridled urban sprawl, turning wetland to concrete land. With wetlands simply paved over, heavy rain couldn’t be easily absorbed, making new neighborhoods extremely vulnerable to flooding.

Preliminary research by my research group, which focuses on risk decision-making finds that, among all land use and land cover types in Harris County, developed land has increased fastest, rising from 35% of the county’s land in 2000 to 50% in 2020.

Harvey was a vivid example of the importance of planning for storm water in urban development. Yet, as the storm’s devastation fades in the collective memory, more people are moving to Houston.

With such high concentrations of people and infrastructure in the coastal region, more people are in harm’s way. More people means that when a disaster strikes, the impact can be much larger than it was just a few decades ago.

Preparing for future disasters

Coastal communities can’t afford to wait for a disaster’s wake-up call to invest in protecting themselves. To prepare for future disasters, I believe they need to rethink urban development with climate change in mind.

Increasing resilience includes improving flood control infrastructure and enhancing emergency response capabilities with worsening storms in mind. It also involves adopting zoning rules that limit building in flood-prone areas. And it may even involve managed retreat—using buyouts to move some communities to safer ground.

Public education campaigns are also important to raise awareness of disaster risks. Accurate flood risk maps, for example, can motivate people to buy insurance, choose their locations more carefully, and prepare their homes for the local risks. Successful awareness campaigns often partner with grassroots organizations to extend community networks and reach their vulnerable populations to help them prepare.

Wanyun Shao is an associate professor of geography at the University of Alabama.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.