George Carlin’s ‘new’ standup set was not generated by AI. It’s much dumber than that

George Carlin’s comedy was both ahead of its time and timeless. Why else would we keep hearing about it more than 15 years after his death in 2008, at age 71? The pantheon-level comic’s political philosophy, as expressed in a 2005 special, fueled a viral anti-Trump ad during the 2020 election. His material on abortion, from 1996, made the rounds a couple summers ago, after the Dobbs decision imperiled Americans’ right to choose. Now, Carlin’s words are shedding light on the way humans interact with technology in 2024—although this time around, the words are technically not his own. Earlier in January, many folks unfortunately had to learn the word “Dudesy” when a comedy AI with that handle released a new Carlin special entitled, I’m Glad I’m Dead. The AI did not autonomously create this special, of course; it was the brainchild of Dudesy’s creators, former Mad TV star Will Sasso and writer Chad Kultgen, who together host a YouTube show and podcast with Dudesy. (Take one guess what the show is called.) The two humans trained their algorithm-based cohost on five decades’ worth of Carlin’s comedy, and voilà! A whole new hour. Though the original video has since been taken down, the internet is forever, so it lives on. Have a peek below if you must; I promise you won’t feel good about it. I’m Glad I’m Dead generated headlines immediately, well before Carlin’s estate announced it would be suing Dudesy’s creators over the special last week, the New York Times reported. Its existence stirred up debates that have been raging since a deceased Fred Astaire first danced with a Dirt Devil in 1997, and which were complicated by advances in AI over the past few years. Is it ethical to release AI-generated content based on a public figure’s previous work? Is it ethical even to consume content produced this way? And forget about ethical: Should it be legal? These questions became further complicated after a revelation was included in the Times article about the lawsuit. It turns out Dudesy didn’t create the special; a dude did. “The YouTube video ‘I’m Glad I’m Dead’ was completely written by Chad Kultgen,” a spokeswoman for Sasso told the Times. (A spokesperson for Kutgen, the report mentions, did not respond to requests for comment; we may have to wait until the next episode of Dudesy for that.) To watch this video a couple weeks ago was an exercise in determining how well an AI could impersonate a figure like Carlin. To watch it now is something else, an exercise in determining how well a comedian could impersonate AI impersonating a figure like Carlin. It’s only within that second funhouse-mirror-like context that Dudesy’s stunt becomes remotely interesting. The voice on I’m Glad I’m Dead sounds kind of like Carlin but is unmistakably off. Not in the clipped, uncanny-valley way of AI robocalls from “Joe Biden,” but like an impressionist biting off more than they can chew. Anyone talented at vocal imitation, for instance, could probably do some of Arnold Schwarzenegger’s most famous lines well enough to trick the average person; the same imitator reading an entire book in Arnold’s voice, though, would fool no one. Similarly, the best 10 seconds or so of I’m Glad I’m Dead might trick most Carlin aficionados, while listening any longer than that exposes nuances in affect and intonation that ruin the illusion. The only reason the voice doesn’t immediately scan as unreal is because it mimics the special musicality of Carlin’s cadence, along with his signature use of long lists for getting points across. Although Sasso and Kultgen may now have to prove in a court of law that the special is not in fact AI-generated, it shouldn’t be too difficult. The content is a dead giveaway that technology did not magically imbue an AI with Carlin’s Ginsu-sharp satirical gaze. In no universe would a George Carlin who set foot in 2024 devote a chunk of his material to America’s obsession with Taylor Swift’s sex life—even accounting for variables like if somehow no other comic had gotten there before him. Only a person doing a crappy impression of Carlin’s material might suggest he would. I’m Glad I’m Dead definitively does not sound like the real Carlin. But only after knowing that Kultgen wrote the special himself does it not sound like real AI either. Common knowledge about AI is constantly in flux, so there is very little consensus around what it can and cannot do, and how well or poorly it can execute. That gray area has caused a lot of concern over AI imitating people, while perhaps not generating enough concern in the other direction. We have gotten so deep in the weeds over the question of what is really real that we may have given short shrift to the question of what is really fake. The Horse_ebooks Twitter account, inescapable during the early 2010s, was a performance art piece that was ahead of its time (if not to the same extent as Carlin). The account gained popularity because its suppose

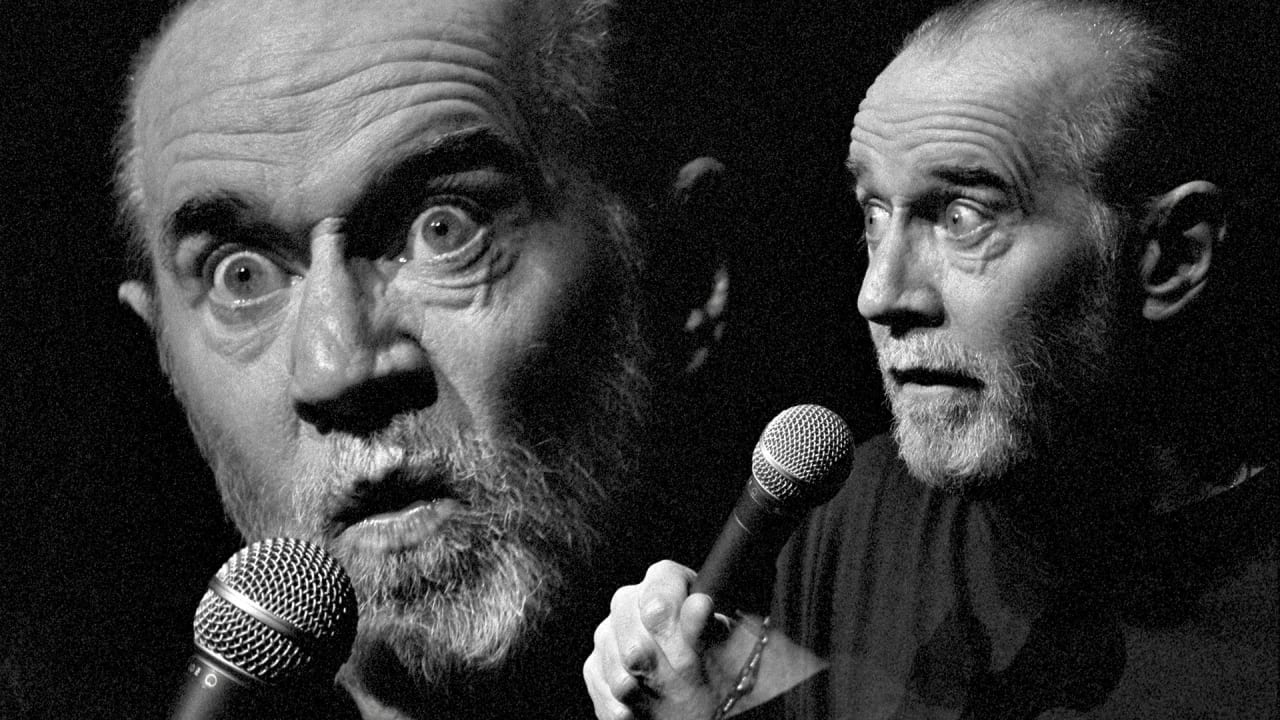

George Carlin’s comedy was both ahead of its time and timeless. Why else would we keep hearing about it more than 15 years after his death in 2008, at age 71?

The pantheon-level comic’s political philosophy, as expressed in a 2005 special, fueled a viral anti-Trump ad during the 2020 election. His material on abortion, from 1996, made the rounds a couple summers ago, after the Dobbs decision imperiled Americans’ right to choose. Now, Carlin’s words are shedding light on the way humans interact with technology in 2024—although this time around, the words are technically not his own.

Earlier in January, many folks unfortunately had to learn the word “Dudesy” when a comedy AI with that handle released a new Carlin special entitled, I’m Glad I’m Dead. The AI did not autonomously create this special, of course; it was the brainchild of Dudesy’s creators, former Mad TV star Will Sasso and writer Chad Kultgen, who together host a YouTube show and podcast with Dudesy. (Take one guess what the show is called.) The two humans trained their algorithm-based cohost on five decades’ worth of Carlin’s comedy, and voilà! A whole new hour.

Though the original video has since been taken down, the internet is forever, so it lives on. Have a peek below if you must; I promise you won’t feel good about it.

I’m Glad I’m Dead generated headlines immediately, well before Carlin’s estate announced it would be suing Dudesy’s creators over the special last week, the New York Times reported. Its existence stirred up debates that have been raging since a deceased Fred Astaire first danced with a Dirt Devil in 1997, and which were complicated by advances in AI over the past few years. Is it ethical to release AI-generated content based on a public figure’s previous work? Is it ethical even to consume content produced this way? And forget about ethical: Should it be legal?

These questions became further complicated after a revelation was included in the Times article about the lawsuit. It turns out Dudesy didn’t create the special; a dude did.

“The YouTube video ‘I’m Glad I’m Dead’ was completely written by Chad Kultgen,” a spokeswoman for Sasso told the Times. (A spokesperson for Kutgen, the report mentions, did not respond to requests for comment; we may have to wait until the next episode of Dudesy for that.)

To watch this video a couple weeks ago was an exercise in determining how well an AI could impersonate a figure like Carlin. To watch it now is something else, an exercise in determining how well a comedian could impersonate AI impersonating a figure like Carlin. It’s only within that second funhouse-mirror-like context that Dudesy’s stunt becomes remotely interesting.

The voice on I’m Glad I’m Dead sounds kind of like Carlin but is unmistakably off. Not in the clipped, uncanny-valley way of AI robocalls from “Joe Biden,” but like an impressionist biting off more than they can chew. Anyone talented at vocal imitation, for instance, could probably do some of Arnold Schwarzenegger’s most famous lines well enough to trick the average person; the same imitator reading an entire book in Arnold’s voice, though, would fool no one. Similarly, the best 10 seconds or so of I’m Glad I’m Dead might trick most Carlin aficionados, while listening any longer than that exposes nuances in affect and intonation that ruin the illusion.

The only reason the voice doesn’t immediately scan as unreal is because it mimics the special musicality of Carlin’s cadence, along with his signature use of long lists for getting points across. Although Sasso and Kultgen may now have to prove in a court of law that the special is not in fact AI-generated, it shouldn’t be too difficult. The content is a dead giveaway that technology did not magically imbue an AI with Carlin’s Ginsu-sharp satirical gaze. In no universe would a George Carlin who set foot in 2024 devote a chunk of his material to America’s obsession with Taylor Swift’s sex life—even accounting for variables like if somehow no other comic had gotten there before him. Only a person doing a crappy impression of Carlin’s material might suggest he would.

I’m Glad I’m Dead definitively does not sound like the real Carlin. But only after knowing that Kultgen wrote the special himself does it not sound like real AI either.

Common knowledge about AI is constantly in flux, so there is very little consensus around what it can and cannot do, and how well or poorly it can execute. That gray area has caused a lot of concern over AI imitating people, while perhaps not generating enough concern in the other direction. We have gotten so deep in the weeds over the question of what is really real that we may have given short shrift to the question of what is really fake.

The Horse_ebooks Twitter account, inescapable during the early 2010s, was a performance art piece that was ahead of its time (if not to the same extent as Carlin). The account gained popularity because its supposedly randomized snippets of equine literature evinced a strange poeticism. People were drawn to Horse_ebooks because its ethereal, cryptic tweets seemed curated by a higher power with a grand design, rather than by a bot. Of course, in 2013, it turned out the tweets actually stemmed from the grand design of human BuzzFeed employee, Jacob Bakkila, who had written them to make a point about [gestures vaguely at the world of 2011].

In the years since, the benefits of pretending to be a bot have become more obvious. The main one seems to be creating attention, rather than art, although the two are often indistinguishable.

In 2018, comedian Keaton Patti claimed to have trained a bot to write romantic comedies using scripts from the rom-com canon. The results were hilariously disjointed and stupid. They were also fake because no such technology existed back then—or if it did, it was certainly not readily available to the average comedy writer. The stunt went so viral that Keaton got a book deal out of it. More importantly, though, it anticipated a cottage industry of similar experiments when the technology to perform such stunts finally did become available in 2022.

Now that it is very much possible to create a song in the style of Nick Cave or an episode of The West Wing using AI, there is just as much incentive in merely pretending to do so.

People tend to be as entertained by the hilarious ineptitude of bad AI creations as they are impressed by the quality of good AI creations. It’s all in the eye of the beholder. Whether a fake-AI piece is accurate, though, matters far less than whether it’s funny or interesting in terms of getting attention, and there is value in that. Need proof? We now all know the word “Dudesy.”

For Sasso and Kultgen’s sake, I hope it was worth getting sued over.