Biden is the most pro-union president since Roosevelt. But he’s not perfect

President Joe Biden has pledged repeatedly to go further than any of his predecessors with his support for U.S. labor rights. “I intend to be the most pro-union president leading the most pro-union administration in American history,” Biden said at a White House meeting in September 2021 that brought together ordinary workers, labor leaders and government officials. He has expressed this intention many times, sometimes clarifying his goals. For example, in 2023 he said in Chicago that his administration was “making it easier to empower workers by making it easier to join a union.” Based on my research regarding the history of organized labor in America, I would give Biden an A-minus for his record on workers rights. In my view, the man dubbed “Union Joe” has lived up to the claim, with one notable error. Four years of sticking to that message Biden has set many precedents related to organized labor. In 2021, Biden encouraged workers at an Amazon facility in Alabama to vote in favor of joining a union. In a video message, he asserted that there should be “no intimidation, no coercion, no threats, no anti-union propaganda” from employers toward unionizing efforts. Although those workers chose not to join the union, this address marked a milestone. No president had ever issued such a statement on behalf of a union during an organizing campaign. In 2022, Biden used executive orders to improve conditions for work on federal projects, including the use of project labor agreements for federal construction projects, which requires the hiring of unionized workers. His administration also created new rules around pay equity for federal workers. And a Biden labor task force also released a report laying out 70 policies the government could implement to strengthen labor unions. In 2023, he became the first president to walk a picket line, which happened during the most effective United Auto Workers strike in decades. The historical record indicates that no prior president had ever even considered taking such an action. In 2024, the Biden administration has picked up the pace. In the month of April alone, it banned the noncompete clauses that can stop workers from taking another job in their same line of work if they quit, expanded eligibility for overtime pay to people making up to $58,656 a year (up from its current cap of $35,568), and pushed pension funds to only invest in companies that adhere to high labor standards. President Joe Biden reiterated a campaign promise to support the right to organize unions during a 2021 address that warned against employer intimidation. Coordinated policy Under the leadership of Biden’s appointees, the National Labor Relations Board—an independent agency charged with protecting workplace rights—has investigated allegations that Starbucks, the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, and other companies have intimidated their employees to discourage unionization drives. Biden also supports the Protecting the Right to Organize Act, better known as the PRO Act. Lawmakers have introduced this measure three times since 2019, and the House of Representatives has passed it twice. Among other things, this bill would impose significant financial penalties on companies that illegally interfere with their employees’ union rights and would speed up the collective bargaining process after workers win a union election. From left: Wakefield Smith, Edwin S. Smith, and the Chairman J. Warren Madden of the National Labor Relations Board, April 14, 1937 [Photo: Library of Congress] Public sentiment Biden’s administration’s pro-union stance is in tune with public sentiment: Approval ratings for unions are higher than they’ve been in several decades. About 7 in 10 Americans say they support unions, according to polls commissioned by Gallup and the AFL-CIO. This public support might be buoyed by current events. High-profile campaigns among workers employed by Amazon, Starbucks, show business studios, hospitals, and automakers have kept unions in the news—regardless of what the White House is doing. A wide array of workers, from strippers to UPS truck drivers, have made big gains in pay and benefits by flexing their collective power. Teachers were already going on strike before the COVID-19 pandemic. They have continued to assert their right to do so around the country. On the other hand . . . To be sure, some of Biden’s aspirations to improve the lot of workers remain unfulfilled. The share of U.S. workers who belong to unions has continued to fall, slipping to 10% in 2023. The buying power of the federal minimum wage, stuck at $7.25 per hour since 2009, has been further eroded due to inflation. Several states, meanwhile, have weakened their child labor laws even as the numbers of undocumented children and teens holding dangerous jobs that are off-limits for minors rise. In terms of Biden’s actions, the low point came in 2022

President Joe Biden has pledged repeatedly to go further than any of his predecessors with his support for U.S. labor rights.

“I intend to be the most pro-union president leading the most pro-union administration in American history,” Biden said at a White House meeting in September 2021 that brought together ordinary workers, labor leaders and government officials.

He has expressed this intention many times, sometimes clarifying his goals.

For example, in 2023 he said in Chicago that his administration was “making it easier to empower workers by making it easier to join a union.”

Based on my research regarding the history of organized labor in America, I would give Biden an A-minus for his record on workers rights. In my view, the man dubbed “Union Joe” has lived up to the claim, with one notable error.

Four years of sticking to that message

Biden has set many precedents related to organized labor.

In 2021, Biden encouraged workers at an Amazon facility in Alabama to vote in favor of joining a union. In a video message, he asserted that there should be “no intimidation, no coercion, no threats, no anti-union propaganda” from employers toward unionizing efforts.

Although those workers chose not to join the union, this address marked a milestone. No president had ever issued such a statement on behalf of a union during an organizing campaign.

In 2022, Biden used executive orders to improve conditions for work on federal projects, including the use of project labor agreements for federal construction projects, which requires the hiring of unionized workers. His administration also created new rules around pay equity for federal workers.

And a Biden labor task force also released a report laying out 70 policies the government could implement to strengthen labor unions.

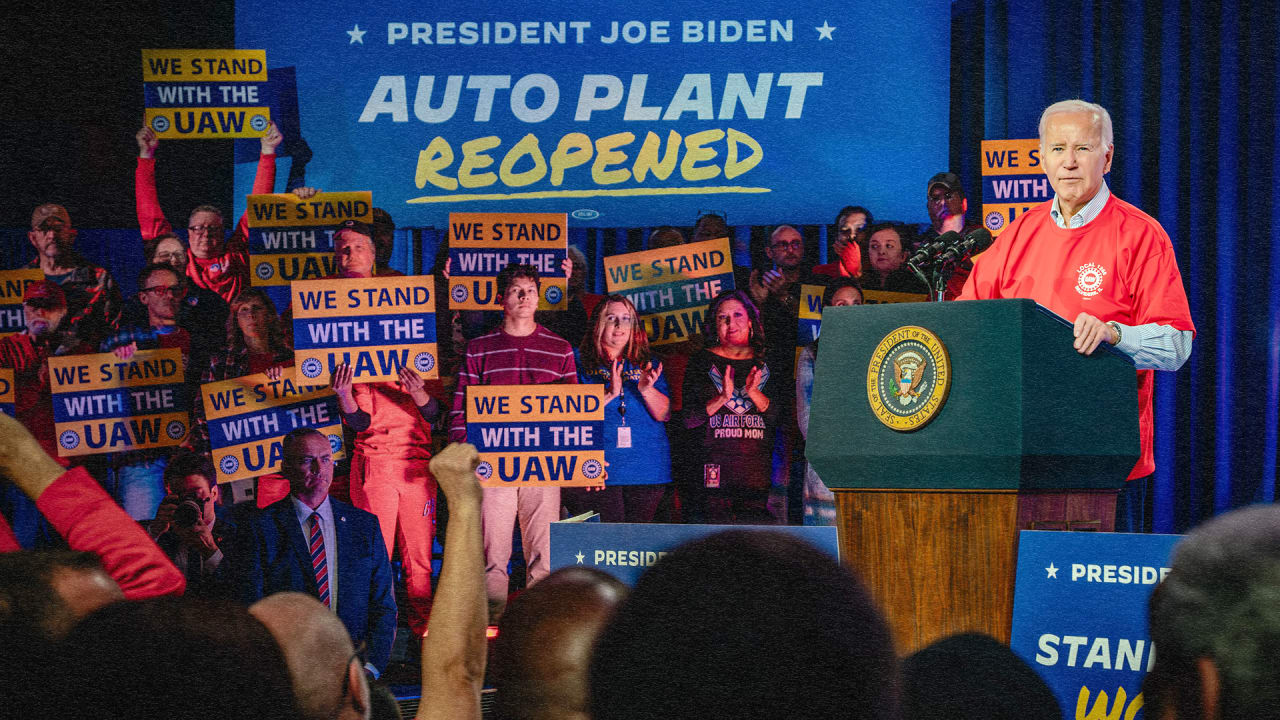

In 2023, he became the first president to walk a picket line, which happened during the most effective United Auto Workers strike in decades. The historical record indicates that no prior president had ever even considered taking such an action.

In 2024, the Biden administration has picked up the pace.

In the month of April alone, it banned the noncompete clauses that can stop workers from taking another job in their same line of work if they quit, expanded eligibility for overtime pay to people making up to $58,656 a year (up from its current cap of $35,568), and pushed pension funds to only invest in companies that adhere to high labor standards.

Coordinated policy

Under the leadership of Biden’s appointees, the National Labor Relations Board—an independent agency charged with protecting workplace rights—has investigated allegations that Starbucks, the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, and other companies have intimidated their employees to discourage unionization drives.

Biden also supports the Protecting the Right to Organize Act, better known as the PRO Act. Lawmakers have introduced this measure three times since 2019, and the House of Representatives has passed it twice.

Among other things, this bill would impose significant financial penalties on companies that illegally interfere with their employees’ union rights and would speed up the collective bargaining process after workers win a union election.

Public sentiment

Biden’s administration’s pro-union stance is in tune with public sentiment: Approval ratings for unions are higher than they’ve been in several decades.

About 7 in 10 Americans say they support unions, according to polls commissioned by Gallup and the AFL-CIO.

This public support might be buoyed by current events.

High-profile campaigns among workers employed by Amazon, Starbucks, show business studios, hospitals, and automakers have kept unions in the news—regardless of what the White House is doing.

A wide array of workers, from strippers to UPS truck drivers, have made big gains in pay and benefits by flexing their collective power.

Teachers were already going on strike before the COVID-19 pandemic. They have continued to assert their right to do so around the country.

On the other hand . . .

To be sure, some of Biden’s aspirations to improve the lot of workers remain unfulfilled.

The share of U.S. workers who belong to unions has continued to fall, slipping to 10% in 2023. The buying power of the federal minimum wage, stuck at $7.25 per hour since 2009, has been further eroded due to inflation.

Several states, meanwhile, have weakened their child labor laws even as the numbers of undocumented children and teens holding dangerous jobs that are off-limits for minors rise.

In terms of Biden’s actions, the low point came in 2022, when he used the Railway Labor Act of 1926 to stop the railroad union from striking for better sick leave. Biden officials argued that the economy could not afford a rail shutdown, but political considerations around inflation before the midterm elections probably contributed to the administration’s response.

At the same time, the Biden administration continued working behind the scenes to pressure rail companies to grant the workers their demands, and they largely did. Union leaders credit Biden for helping them get this victory for their workers.

Congress and the Supreme Court

There is only so much any president can do to promote labor rights. As with any other cause, they’re limited by the broader political climate and economic realities.

Given the generally weak track record of his predecessors going back to the late 1940s, I would argue that Biden is the most pro-union president since Franklin D. Roosevelt.

FDR, however, had enormous majorities in Congress when he signed into law two measures that safeguard U.S. labor rights to this day: the National Labor Relations Act, which protects the right of private sector workers to organize unions without fear of retaliation, and the Fair Labor Standards Act, which established a minimum wage and made most child labor illegal.

Biden, in contrast, has had to contend with a narrow Democratic majority in the Senate throughout his presidency, and the Republicans gained a slim House majority in the 2022 midterm elections.

He’s also seeking to expand labor rights at a time when the Supreme Court’s conservative majority has been consistently ruling against unions.

To be sure, there are several significant labor cases that could potentially land on the Supreme Court’s docket. It will take time to see if unions become more powerful thanks to Biden’s actions and their own organizing, or whether the court continues to erode labor laws.

That’s because historically, U.S. judges have had at least as much say in determining labor rights as presidents.

Erik Loomis is a professor of history at the University of Rhode Island.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.