Apple was a smart-speaker laggard, but its strategy is working

When Apple got into the smart-speaker business with the HomePod four years ago with a sharp focus on music, it seemed to be miles behind Amazon and Google. Those companies had spent years tacking on new features to their Alexa and Google Assistant speakers, and they had a long head start on integrating smart home devices. They’d even enlisted developers to create third-party voice skills so that users could order a Domino’s pizza or call for an Uber without lifting a finger. I admit that I bought the idea that they were building a post-phone ecosystem, and that Apple was a laggard. But over time, that sprawling array of features has started to become a liability. Data reported on recently by Bloomberg—along with my own anecdotal experience—shows that people don’t often use their smart speakers for much beyond music and timers, and that doesn’t leave Amazon and Google with great business prospects for the speakers they’ve sold at thin-to-negative profit margins. Their attempts to clue people in to profitable features—for instance, with Alexa blurting out shopping offers in response to unrelated queries—tend to come off as unwelcome intrusions. All of which puts Apple in a surprisingly strong position despite its late start. While the company’s market share is far lower than that of Amazon and Google, its narrower ambitions with HomePod are more in line with the way people actually use their smart speakers. Now that Apple is focusing on cheaper speakers with the HomePod Mini—it discontinued the original HomePod three years after launch—its focus could help the company win over customers in the long run, especially if Amazon’s and Google’s attempts to monetize their speakers become more desperate. Signs of stagnation As Bloomberg’s Priya Anand reported in December, Amazon has shown some concern with users’ level of engagement with Alexa. Internal planning documents from 2019 stated that within three hours of activating an Alexa device, people discover about half the features they’ll ever end up using, and that new features don’t lead to higher engagement. In some years, Amazon’s data showed that 15% to 25% of users become inactive after two weeks, and most users were only using their speakers for music and timers. Amazon disputed the report, telling Bloomberg that the metrics it cited are out of date, and that it’s seen increases in customer usage. Still, the story should ring true for a lot of people who own smart speakers. My house, for instance, is filled with speakers from Amazon, Apple, and Google—acquired partly to fulfill my duties as a tech journalist and partly because they’re so often on sale for peanuts. I’ve got speakers in the living room, the bedroom, the basement, and my office, and there’s even an Echo Auto in my car. I think I qualify as a power user and am well aware of the many features these devices offer. Yet I can count on two hands the number of functions for which I use these smart speakers with any regularity: Playing music or ambient noise Setting timers, alarms, and reminders Adding items to a grocery list Creating calendar appointments Controlling a few smart home devices Asking for basic information, like the weather or sports scores Intercom functionality between speakers Looking at family photos (on the smart displays) To be fair, smart speakers are great for those tasks. They don’t require much attention, and they’re faster to execute by voice than with a phone or computer. Still, I’m not planning to use these features any more frequently than I do now, and I don’t feel compelled to branch out into new use cases. I’m not interested in playing trivia games or listening to random jokes on smart speakers (there are plenty of better ways to pass the time). And ordering products by voice can quickly become a frustrating exercise. The problem for Amazon and Google is that nearly all the above tasks are interchangeable among voice assistants, and Apple has caught up on most of them. I can ask any voice assistant for the weather, a timer, or music and get pretty much the same results. HomePod speakers can now distinguish between users’ voices just like Alexa and Google Assistant can. And in 2020, Apple added intercom features to match those of its rivals. In other areas, Amazon and Google may be realizing that they’ve spread themselves too thin. In November, Amazon discontinued Alexa’s email-checking feature, and along with it the ability to track the status of non-Amazon packages. It also wound down a partnership with Microsoft that allowed Alexa and Cortana to talk with one another. Google, meanwhile, eliminated Assistant’s “Your News Update” feature, which summarized the news from a variety of sources. (The company had announced it two years earlier with great fanfare, drawing parallels to the launch of Google News in the early aughts.) Even smart home compatibility isn’t much of a differentiator anymore. While Amazon and Google used to brag about how many light bulbs and door lock

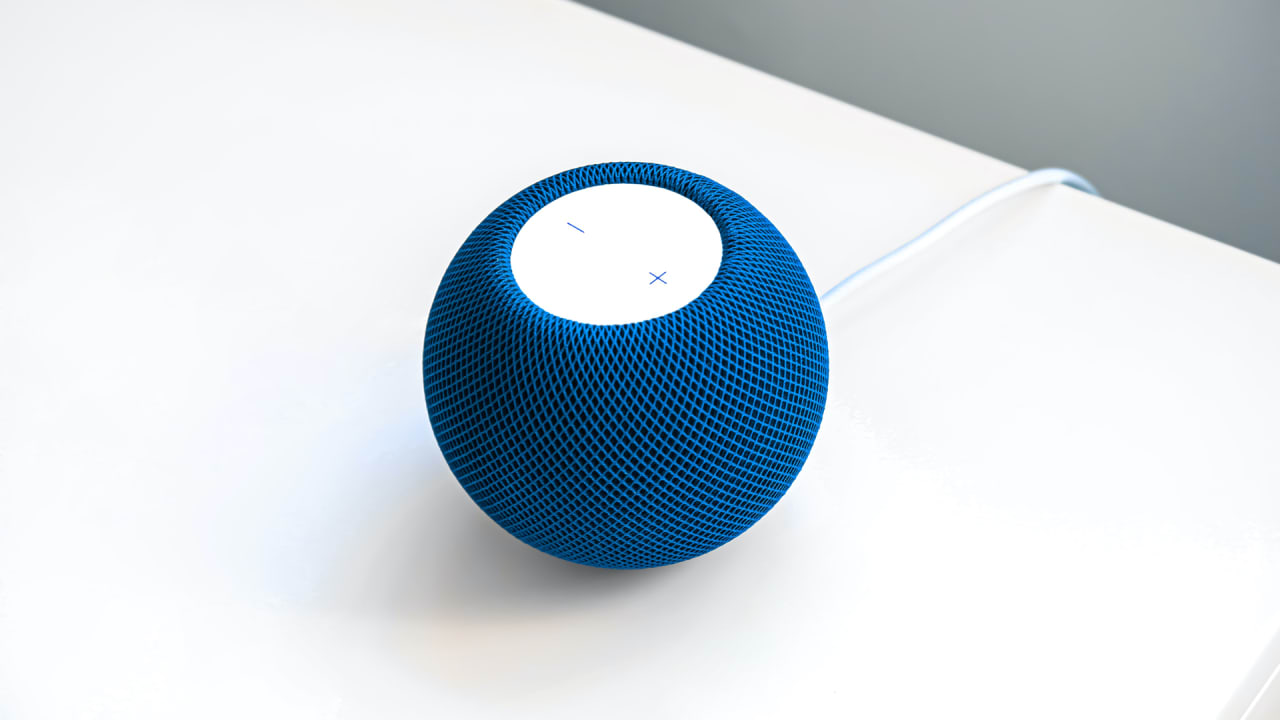

When Apple got into the smart-speaker business with the HomePod four years ago with a sharp focus on music, it seemed to be miles behind Amazon and Google.

Those companies had spent years tacking on new features to their Alexa and Google Assistant speakers, and they had a long head start on integrating smart home devices. They’d even enlisted developers to create third-party voice skills so that users could order a Domino’s pizza or call for an Uber without lifting a finger. I admit that I bought the idea that they were building a post-phone ecosystem, and that Apple was a laggard.

But over time, that sprawling array of features has started to become a liability. Data reported on recently by Bloomberg—along with my own anecdotal experience—shows that people don’t often use their smart speakers for much beyond music and timers, and that doesn’t leave Amazon and Google with great business prospects for the speakers they’ve sold at thin-to-negative profit margins. Their attempts to clue people in to profitable features—for instance, with Alexa blurting out shopping offers in response to unrelated queries—tend to come off as unwelcome intrusions.

All of which puts Apple in a surprisingly strong position despite its late start. While the company’s market share is far lower than that of Amazon and Google, its narrower ambitions with HomePod are more in line with the way people actually use their smart speakers. Now that Apple is focusing on cheaper speakers with the HomePod Mini—it discontinued the original HomePod three years after launch—its focus could help the company win over customers in the long run, especially if Amazon’s and Google’s attempts to monetize their speakers become more desperate.

Signs of stagnation

As Bloomberg’s Priya Anand reported in December, Amazon has shown some concern with users’ level of engagement with Alexa.

Internal planning documents from 2019 stated that within three hours of activating an Alexa device, people discover about half the features they’ll ever end up using, and that new features don’t lead to higher engagement. In some years, Amazon’s data showed that 15% to 25% of users become inactive after two weeks, and most users were only using their speakers for music and timers.

Amazon disputed the report, telling Bloomberg that the metrics it cited are out of date, and that it’s seen increases in customer usage. Still, the story should ring true for a lot of people who own smart speakers.

My house, for instance, is filled with speakers from Amazon, Apple, and Google—acquired partly to fulfill my duties as a tech journalist and partly because they’re so often on sale for peanuts. I’ve got speakers in the living room, the bedroom, the basement, and my office, and there’s even an Echo Auto in my car. I think I qualify as a power user and am well aware of the many features these devices offer.

Yet I can count on two hands the number of functions for which I use these smart speakers with any regularity:

- Playing music or ambient noise

- Setting timers, alarms, and reminders

- Adding items to a grocery list

- Creating calendar appointments

- Controlling a few smart home devices

- Asking for basic information, like the weather or sports scores

- Intercom functionality between speakers

- Looking at family photos (on the smart displays)

To be fair, smart speakers are great for those tasks. They don’t require much attention, and they’re faster to execute by voice than with a phone or computer. Still, I’m not planning to use these features any more frequently than I do now, and I don’t feel compelled to branch out into new use cases. I’m not interested in playing trivia games or listening to random jokes on smart speakers (there are plenty of better ways to pass the time). And ordering products by voice can quickly become a frustrating exercise.

The problem for Amazon and Google is that nearly all the above tasks are interchangeable among voice assistants, and Apple has caught up on most of them. I can ask any voice assistant for the weather, a timer, or music and get pretty much the same results. HomePod speakers can now distinguish between users’ voices just like Alexa and Google Assistant can. And in 2020, Apple added intercom features to match those of its rivals.

In other areas, Amazon and Google may be realizing that they’ve spread themselves too thin. In November, Amazon discontinued Alexa’s email-checking feature, and along with it the ability to track the status of non-Amazon packages. It also wound down a partnership with Microsoft that allowed Alexa and Cortana to talk with one another. Google, meanwhile, eliminated Assistant’s “Your News Update” feature, which summarized the news from a variety of sources. (The company had announced it two years earlier with great fanfare, drawing parallels to the launch of Google News in the early aughts.)

Even smart home compatibility isn’t much of a differentiator anymore. While Amazon and Google used to brag about how many light bulbs and door locks hooked into their respective assistants, support for Apple’s HomeKit is becoming more common, and all three ecosystems will be on equal footing when Matter, the smart home connectivity standard, launches later this year. (Incidentally, smart homes themselves seem to be stagnating, in part because their voice-driven interfaces don’t always work that well.)

Apple’s advantage

After all this time, music is still a key selling point for smart speakers, and that’s the one area in which Apple excels. The HomePod Mini sounds great for its size and price, but more important, Apple’s AirPlay-based music system works in ways that Alexa and Google Assistant just don’t.

For one thing, AirPlay speakers have quickly become ubiquitous despite HomePod’s limited market share. Recent TVs from LG, Samsung, Vizio, and Sony can all function as AirPlay receivers, as can all Roku players and smart TVs. Some third-party speakers support AirPlay as well, including those from Sonos. While I own only a single HomePod Mini, I’ve nonetheless accumulated AirPlay speakers in several rooms without even trying.

Apple has created the kind of ecosystem stickiness that has eluded its rivals.

What Apple has created, in other words, is the kind of ecosystem stickiness that has eluded its rivals, and it did so by maintaining its original focus on music. From Apple’s point of view, the HomePod’s otherwise limited features and lack of third-party voice skills may be a benefit rather than a hinderance, especially if it leads to more Apple Music and Apple One subscriptions.

That’s not to say Amazon and Google won’t find business models that stick. Amazon has increasingly turned its attention to security, with Echo speakers and smart displays serving as additional points of surveillance. It monetizes those products through various home-monitoring subscriptions, including Alexa Guard Plus, Alexa Care Hub for eldercare, and Ring Protect Pro. Google’s monetization plans aren’t as clear, though forays into advertising don’t seem far-fetched. But those strategies hinge on getting people to use their smart speakers in ways they didn’t anticipate at the outset.